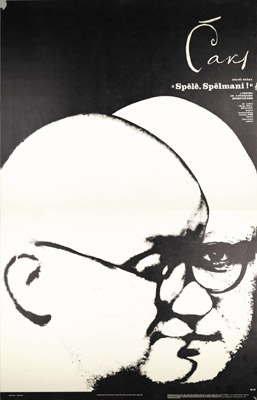

The second play in Pētersons’ Poetry Theatre trilogy (a separate entry on Pētersons’ life and the principles of the Poetry Theatre is included in the Latvian Culture Canon), the fact that it was allowed on the stage at all was a small miracle in itself. “Play, Player!” drew upon the poetry and prose of Aleksandrs Čaks (1901−1950, also included in the Culture Canon), mostly the eponymous long poem written in 1944 and the banned epic poem “Touched by Eternity” (Mūžības skartie, 1940) about Latvian Riflemen who fought for independence during the First World War.

The production accelerated the revival of Čaks’ rightful reputation as a poet of the people, and its 16-season run lasted into the Latvian National Awakening in the 1980s. But for Pētersons personally it came at an impossible time: he had just been sacked as the head of the Daile Theatre, and his eleven-year-old son had died as old film reels stored at their family home caught fire. The poet Imants Ziedonis (1933–2013, also included in the Culture Canon) played an important role in bringing Pētersons out of a deeply depressive state and making the canonical staging a reality.

The two had collaborated earlier – Pētersons used Ziedonis’ writings for the first Poetry Theatre play “Motorcycle” (Motocikls, 1967). Ziedonis managed to invigorate the troubled Pētersons, idling in the Jūrmala resort town at the time, with an idea to stage Čaks, selecting the chief sources for the dramatization from Čaks’ oeuvre and, early on in the production, assuming some of the organisational duties, as Pētersons was still very unwell. “”I cannot leave you alone right now,” Imants said when I asked him to leave as I knew they were waiting for him in Rīga…I will remember this forever,” Pētersons would later write.

After the idea was graciously accepted by the Youth Theatre under Adolf Shapiro (1939, also included in the Culture Canon), the mise en scène started, with Pētersons described as thoroughly open, improvisational and an understandably scattered throughout the process. Judging from the testimonials, it seems as if the recent tragic events had cast him temporarily into something like sainthood, well above rational “oughts” and “ought-nots” that must have always been a reality for a director as well-versed in theory as Pētersons.

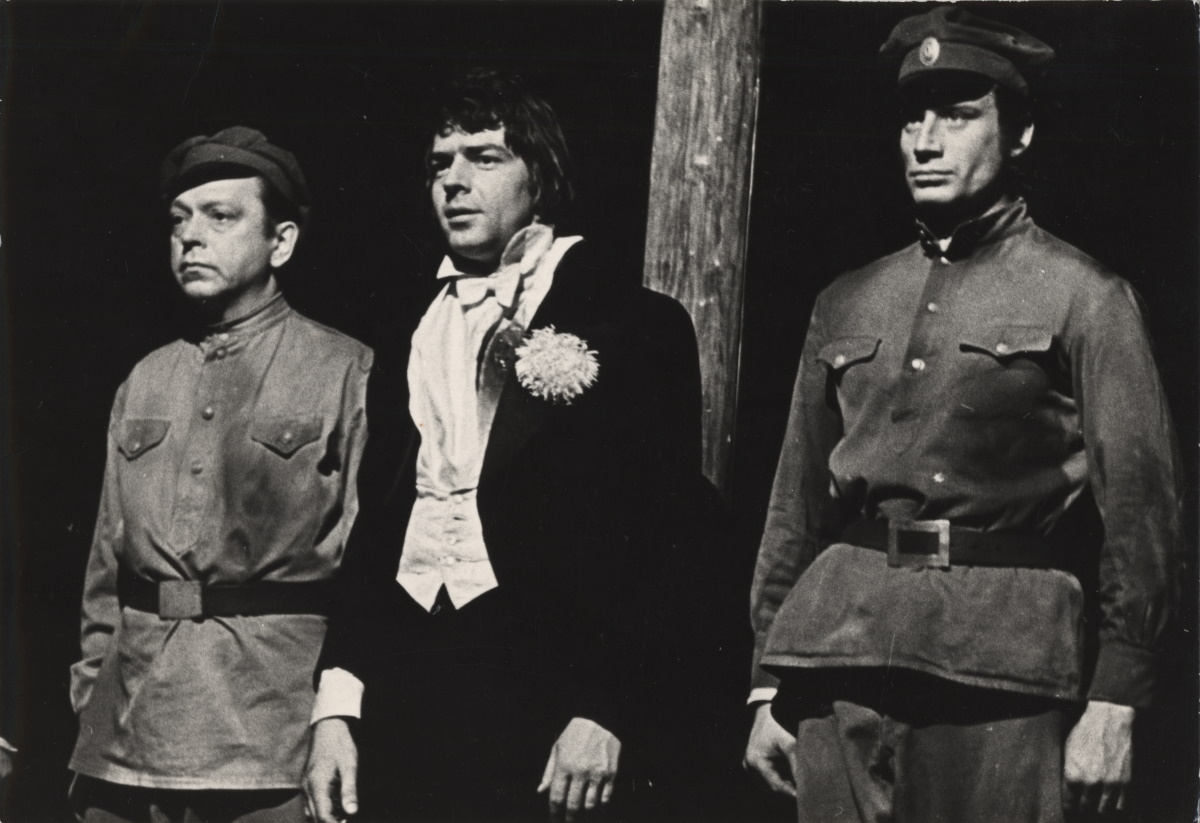

Čaks’ long poem fitted Pētersons very well, as there’s a current centering around the conflict between the artist and the public throughout his work. Dejected and feeling unable to live the life he has made in song, the Poet conceives the Player, an Orphean figure whom he accompanies on a number of adventures. “Play, Player!” culminates in a scene where the Poet sacrifices himself by stepping in front of the blade when an angered country bumpkin tries to stab the Player. And the Player does survive – becoming more real than the Poet, who, having symbolically died, succumbs to the ridicule of the crowd as he struggles to regain mastery over what he created.

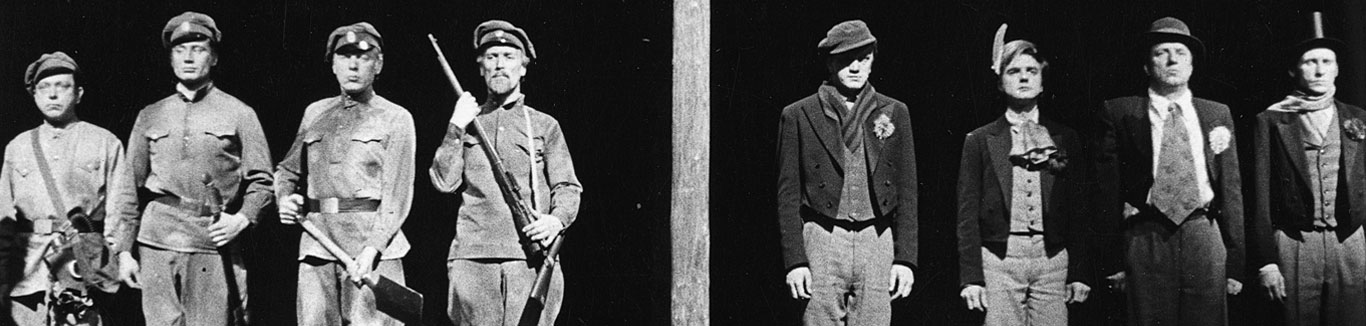

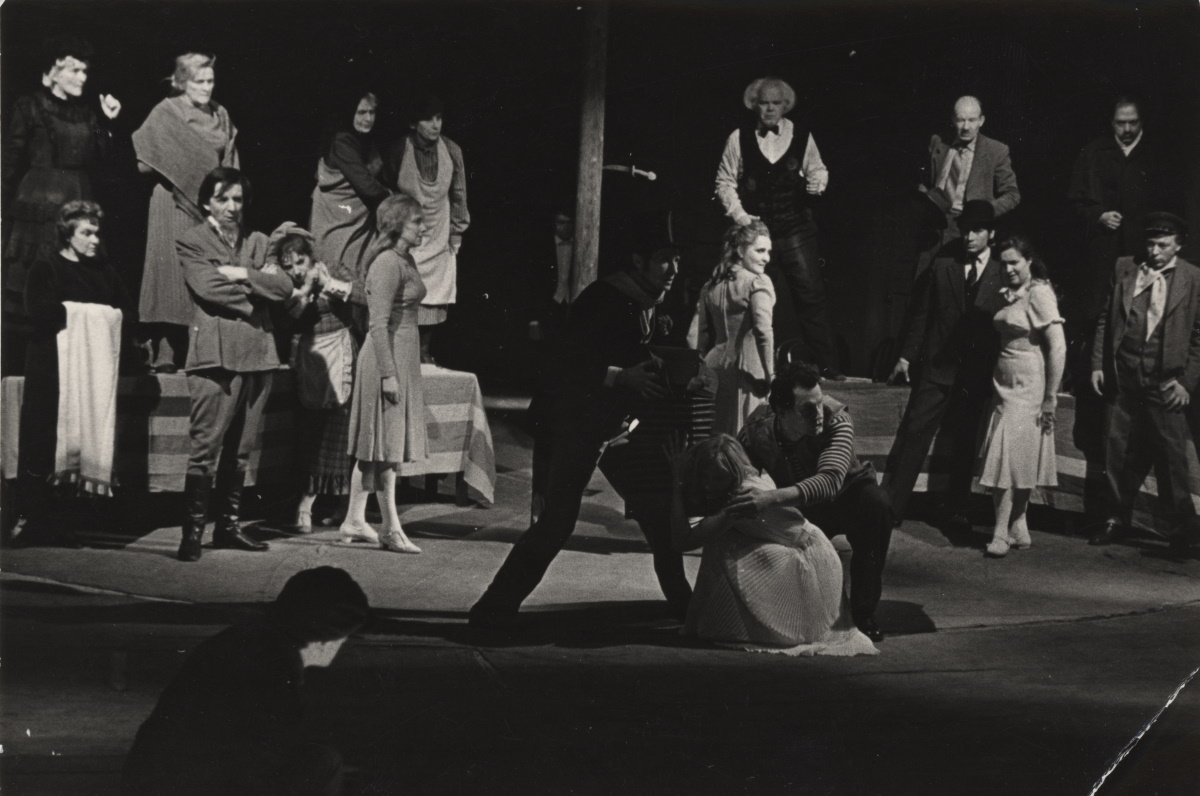

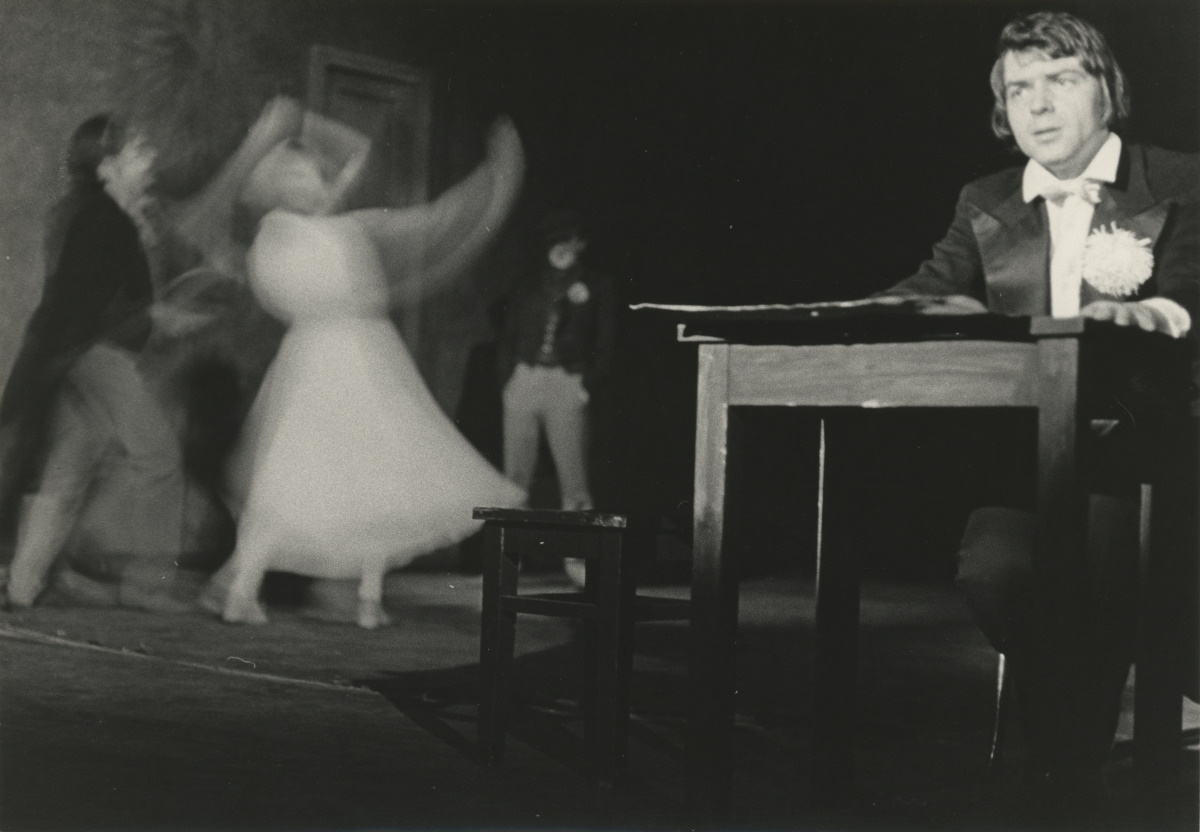

With acclaimed scenographer Ilmārs Blumbergs (1943–2016), Pētersons created an intuitive space with an uncanny apartment scene, based on Čaks’ home in Rīga, turning into a city square with a maypole, an inn, as well as into the yard of a country house as the play progressed. The interior decorations underwent poetic deformations, with huge ink bottles and giant beer mugs seen on stage; meanwhile the excellent choreography culminated as the play ended, with the poet trying to scale the maypole and falling after being booed by the crowd. Phantasmagoric elements and vision-like scenes were supplemented with the appearance of four poetic “meters”, personified on stage by the actors Aleksandrs Maizuks (1928–2000), Jānis Vītoliņš (1937–2000), Andris Mekšs (1941–2018), and Edgars Liepiņš (1929–1995).

The play concluded with the shattered Poet (played by Imants Skrastiņš (1941–2019)) reciting Čaks’ “Confession” (Atzīšanās), one of the most popular love poems in the Latvian language. In the play, the ending refrain, “You’re the Only One I Loved” (Tikai tevi es mīlējis esmu) was taken to refer to love of one’s city, and of one’s country. After this, audiences would often sustain a lengthy silence before bursting into an even lengthier applause. The song’s composer Imants Kalniņš (1941), included in the Culture Canon, wrote for the play have also become part of Latvia’s national heritage.

Pētersons went on to stage another Poetry Theatre production with “Mystery About a Human Being” (Mistērija par Cilvēku, 1974) based on Vladimir Mayakovsky’s writings. Not received as well as “Play, Player!”, it nevertheless cemented Pētersons’ authorial style is remembered as a passionate and intellectually charged production.

Pētersons’ best work came at a crucially important time for Latvian culture, and in addition to revitalizing the dramatic scene he also helped Latvia remember and preserve its heritage, as expressed in the poetry of Čaks.

His plays are still staged today. Latvian theatre directors routinely draw on poetic material for their work, and that they are doing so may on some degree owe to Pētersons.

Lauris Veips