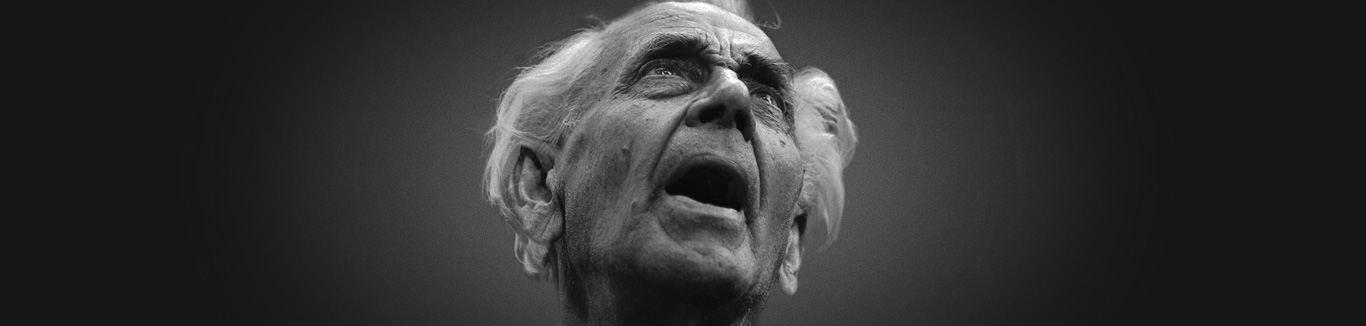

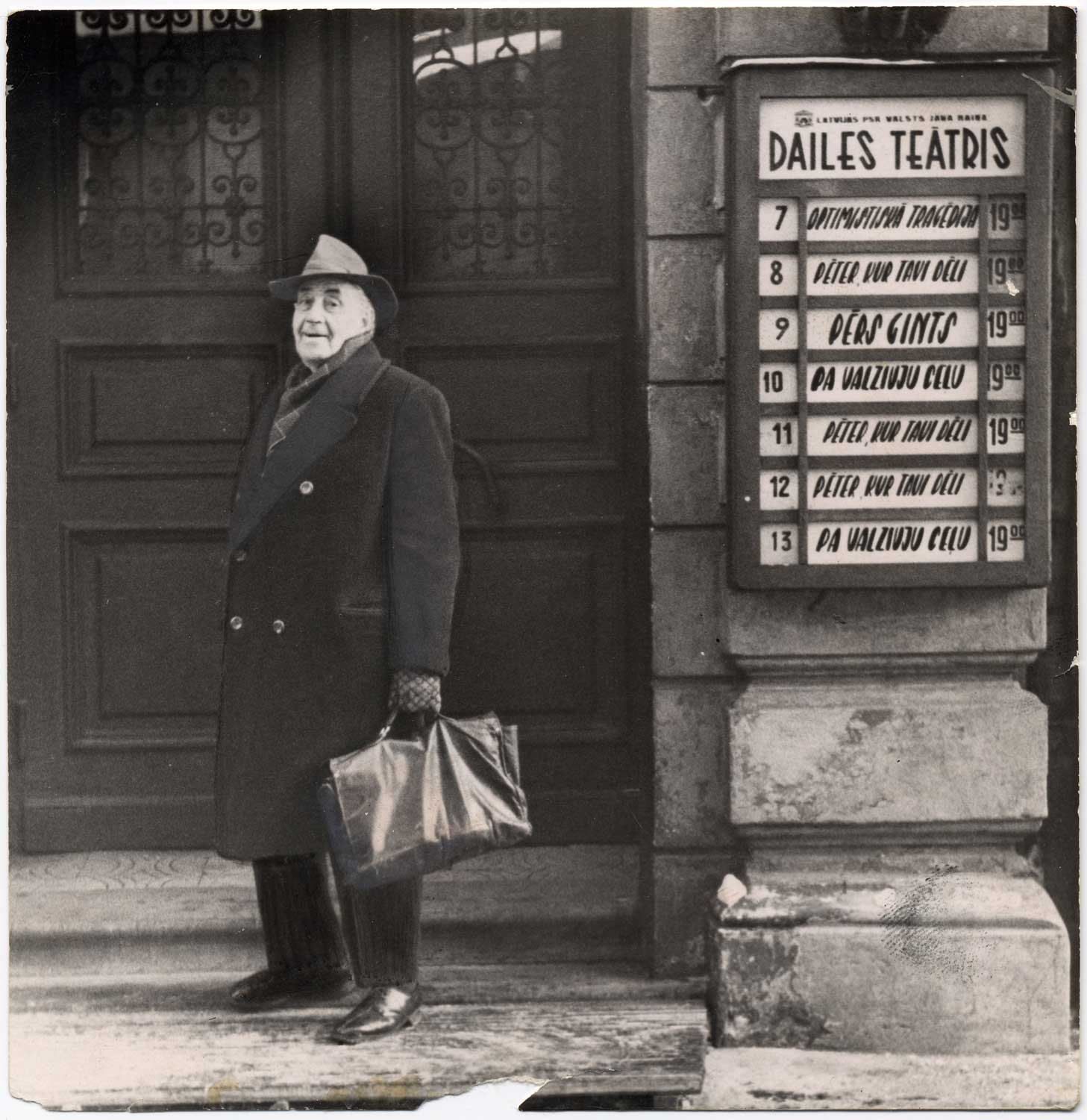

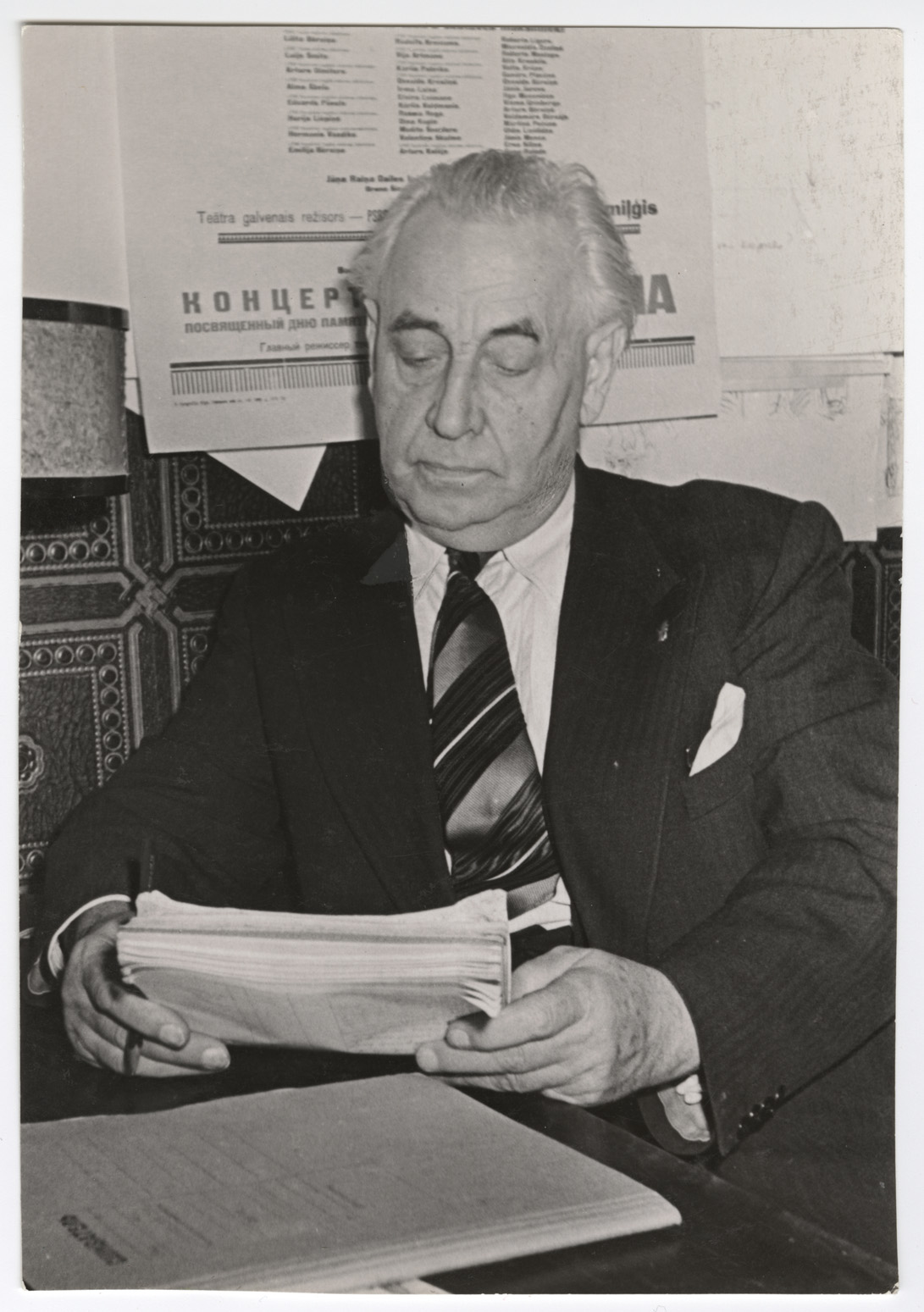

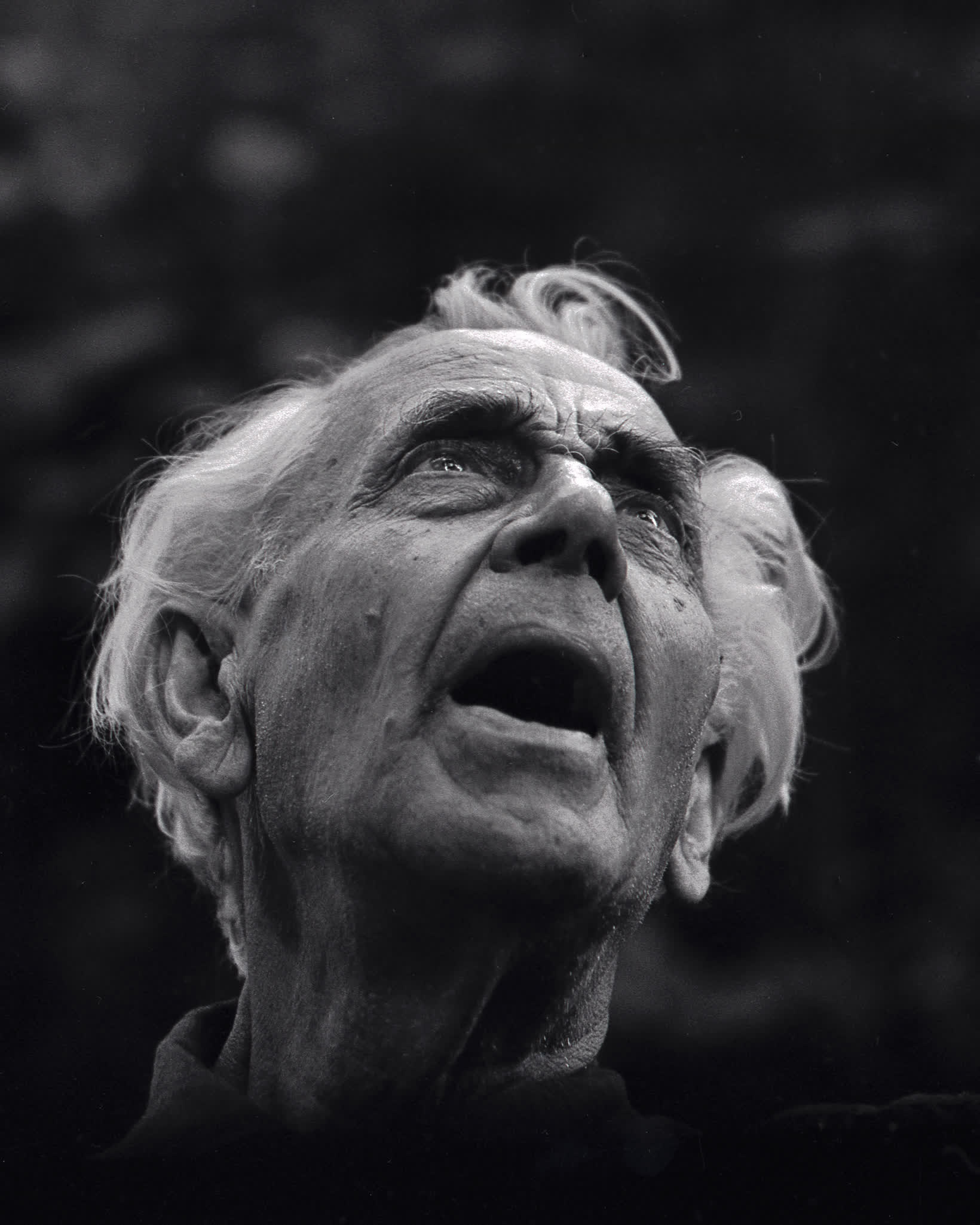

A grandiose portrait of an aged man, with eyes welled up to tears gazing heavenward, adorns the side wall of the New Riga Theatre building in Rīga, Lāčplēša iela 25. It’s Eduards Smiļģis, the founder of the Daile Theatre and a director of passionate intensity. He cuts a towering figure in Latvian theatre. He breathed a symbolist and expressionist spirit onto the Latvian stage, opposing the prevailing trends of realism. Smiļģis set up the Daile Theatre in 1920, at a time when very little was clear about the future of the Latvian state, let alone its art, and lived to see it survive as a powerhouse of modern drama important on a European scale.

Smiļģis was born in Rīga into a working-class family. His first brush with the mysterious, which would come to dominate his work, came when he was a little boy attending a local catholic school: the sacred images he saw there would stay with him all life, according to theatre historian Rita Rotkale (1948). Smiļģis went on to receive an all-round education in the exact sciences. Upon graduation, he took on a well-paid job as a technical designer in the factory “Motor” and started acting at amateur theatres in 1907, making his professional debut in 1910 to scathing reviews.

Nevertheless, Smiļģis quit the factory and joined the troupe of the New Riga Theatre in 1912, earning a name for himself for his heroic roles. He became acquainted with the writer Rainis (1865–1929, included in the Latvian Culture Canon), who became an important figure in establishing the new theatre. Smiļģis would later stage many of Rainis’ plays.

As the First World War broke out, Smiļģis fled to Petrograd (now St Petersburg) where he performed at a Latvian diaspora theatre and saw the finest productions of the Russian avant-garde alongside classic performances. Dizzy from all the impressions, Smiļģis, who had never even tried directing, made plans to set up a new kind of theatre.

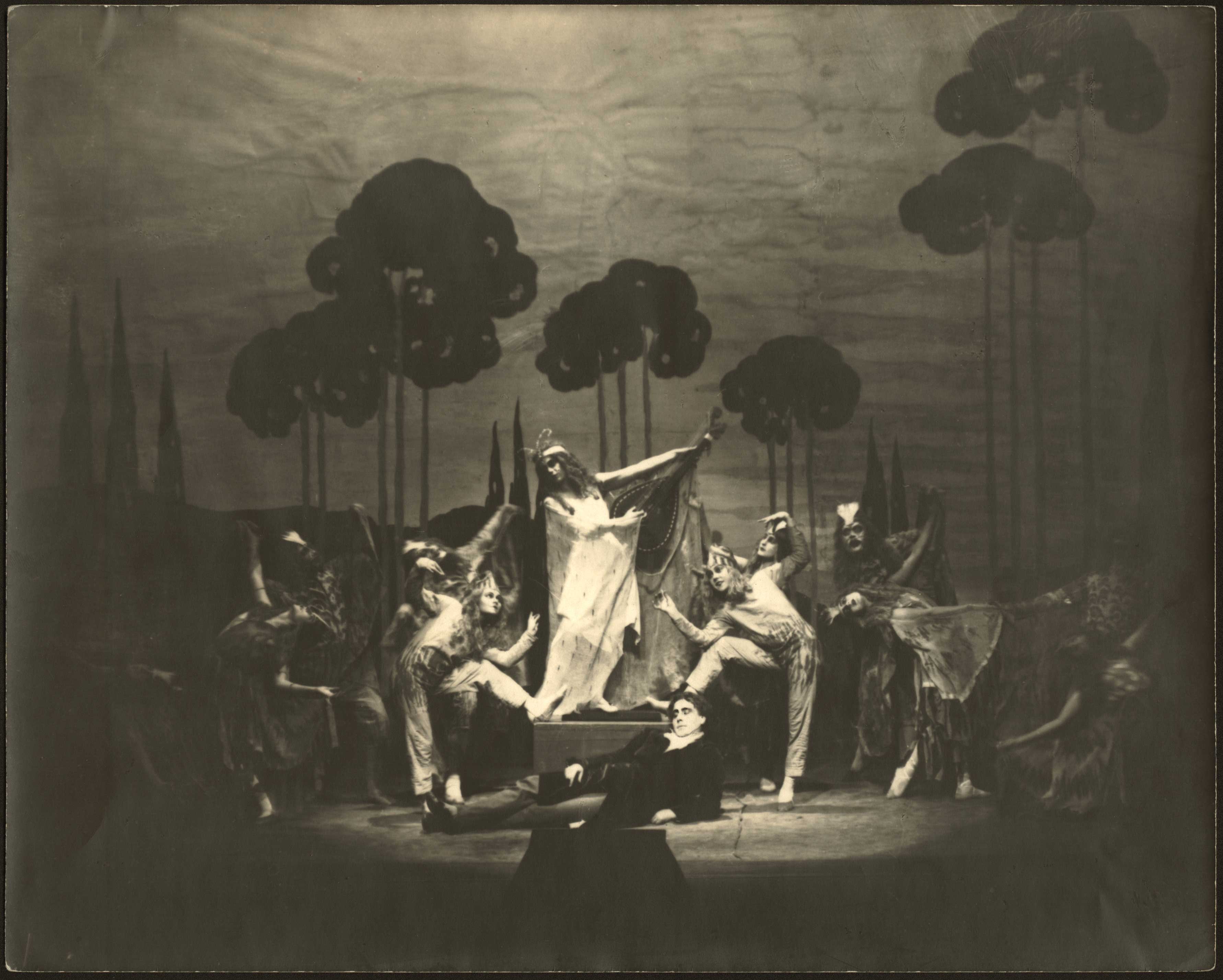

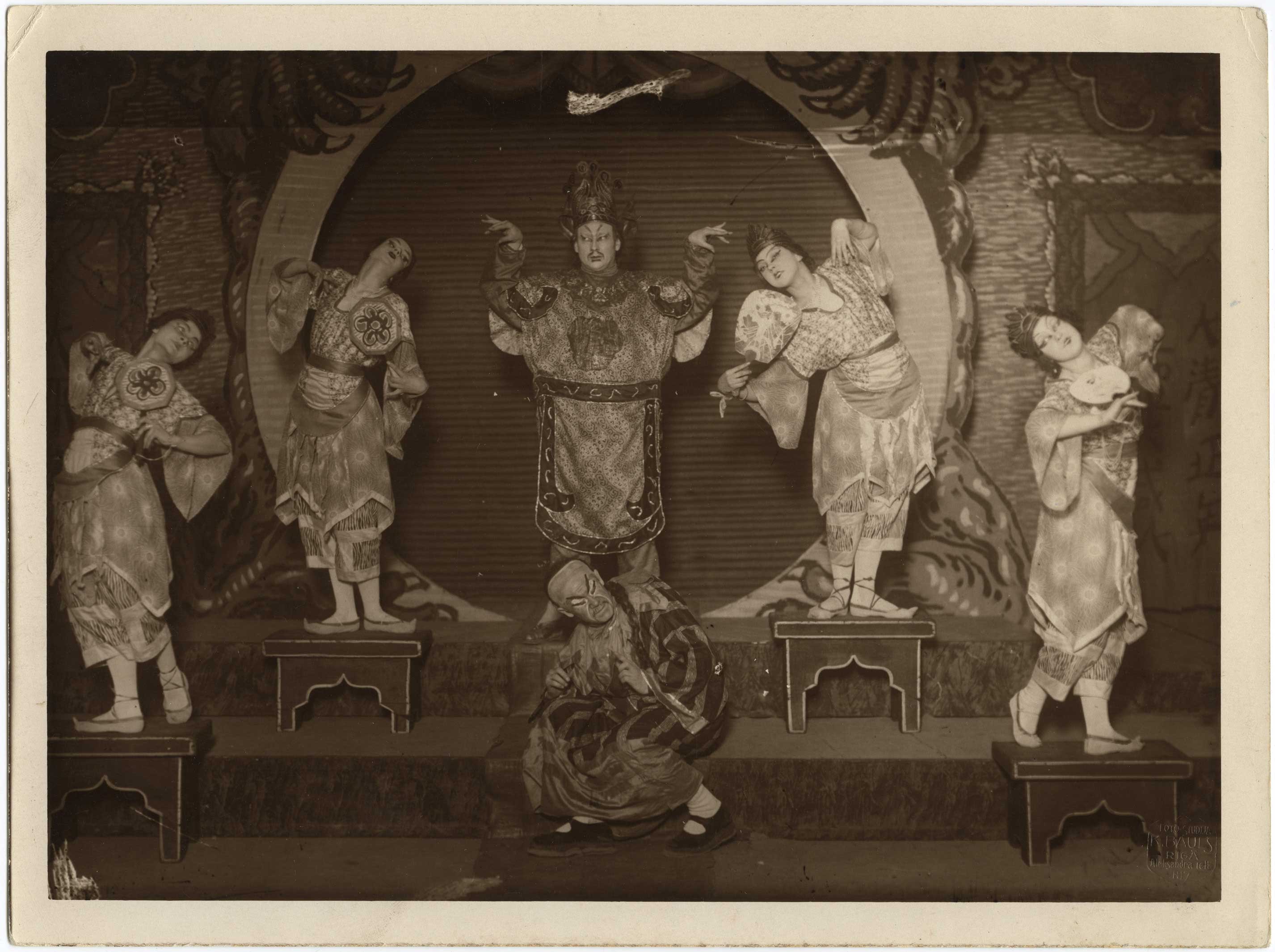

During the evacuation, Smiļģis got to know Jānis Muncis (1886–1955). A disciple of the Russian director Vsevolod Meyerhold (1874–1940), Muncis’ theories and set designs would have a decisive influence on the early Daile Theatre, underpinning its reputation as a pioneering locus of modern drama. While Smiļģis did not meet her there, Felicita Ertnere (1891–1975), a learned physical educator, was also in Petrograd at the time. Ertnere was later instrumental in honing the technical abilities of the Daile Theatre troupe.

Upon his return to Latvia, Smiļģis set to work immediately. Money was scarce in post-war Latvia, and the proposed building, which had earlier housed the New Riga Theatre, was in disrepair. “There were no window panes and no locks. The heating device was rusty…and let’s not speak of the stage and workshop inventory,” the historian Rūdolfs Kokle wrote.

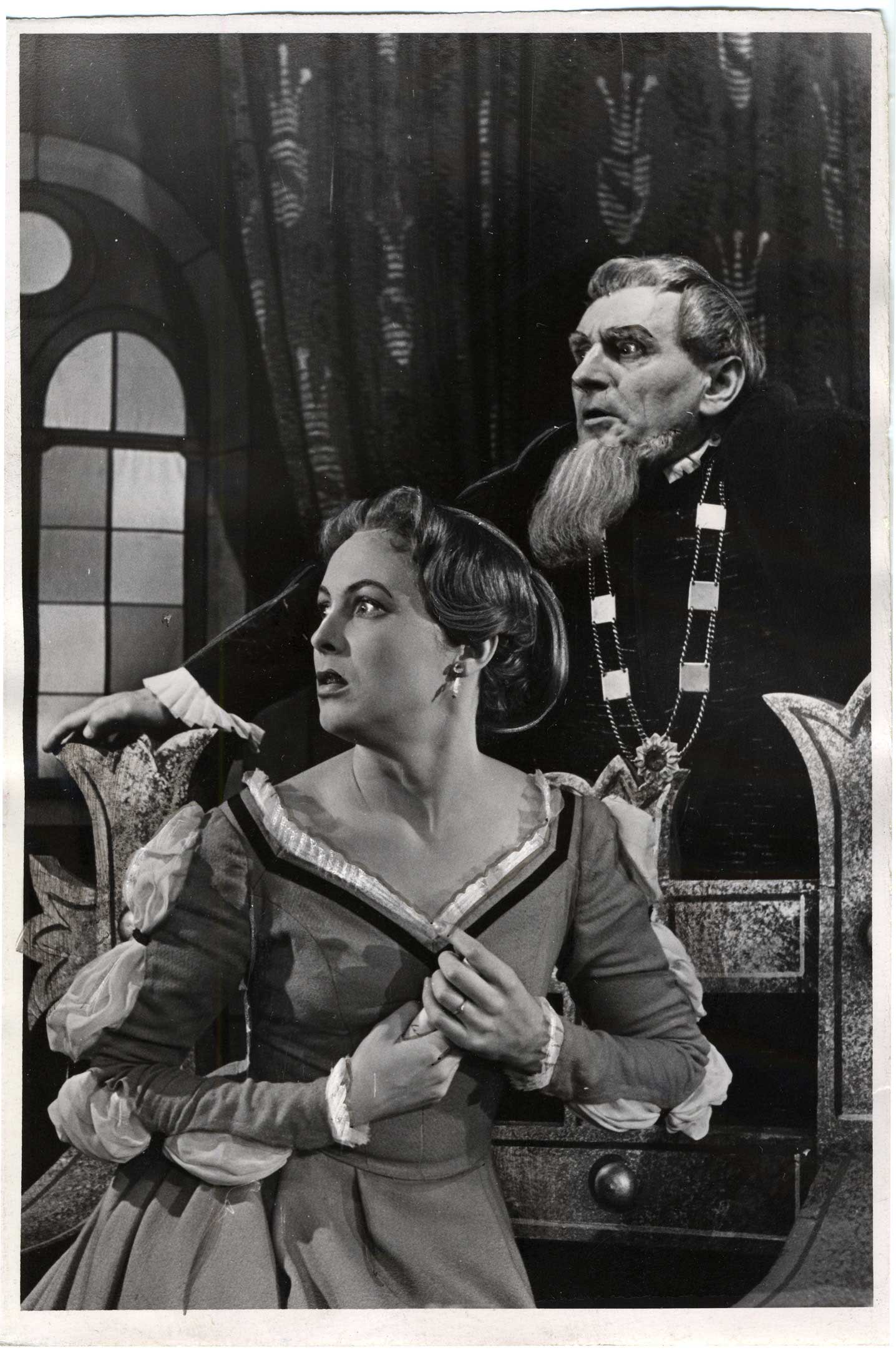

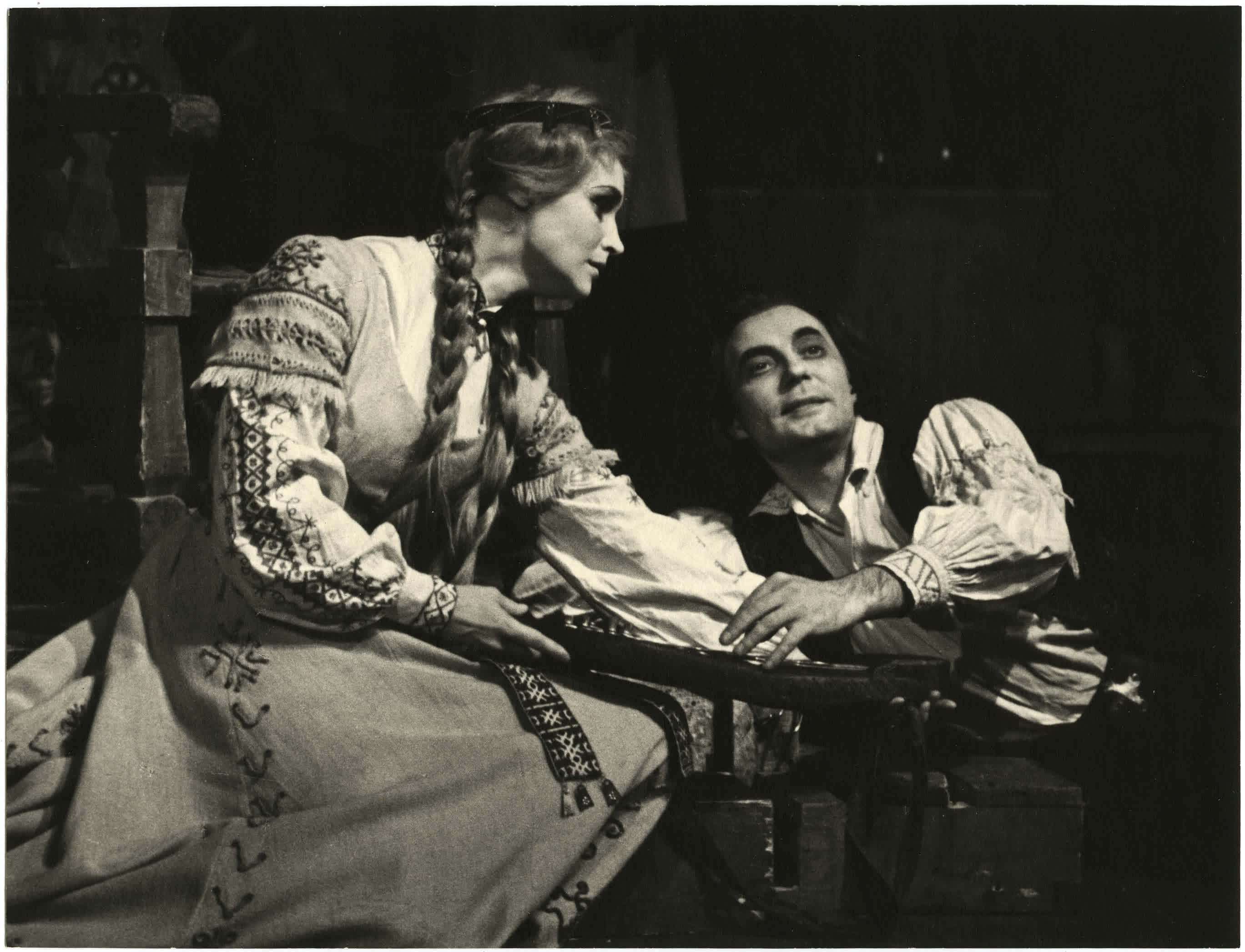

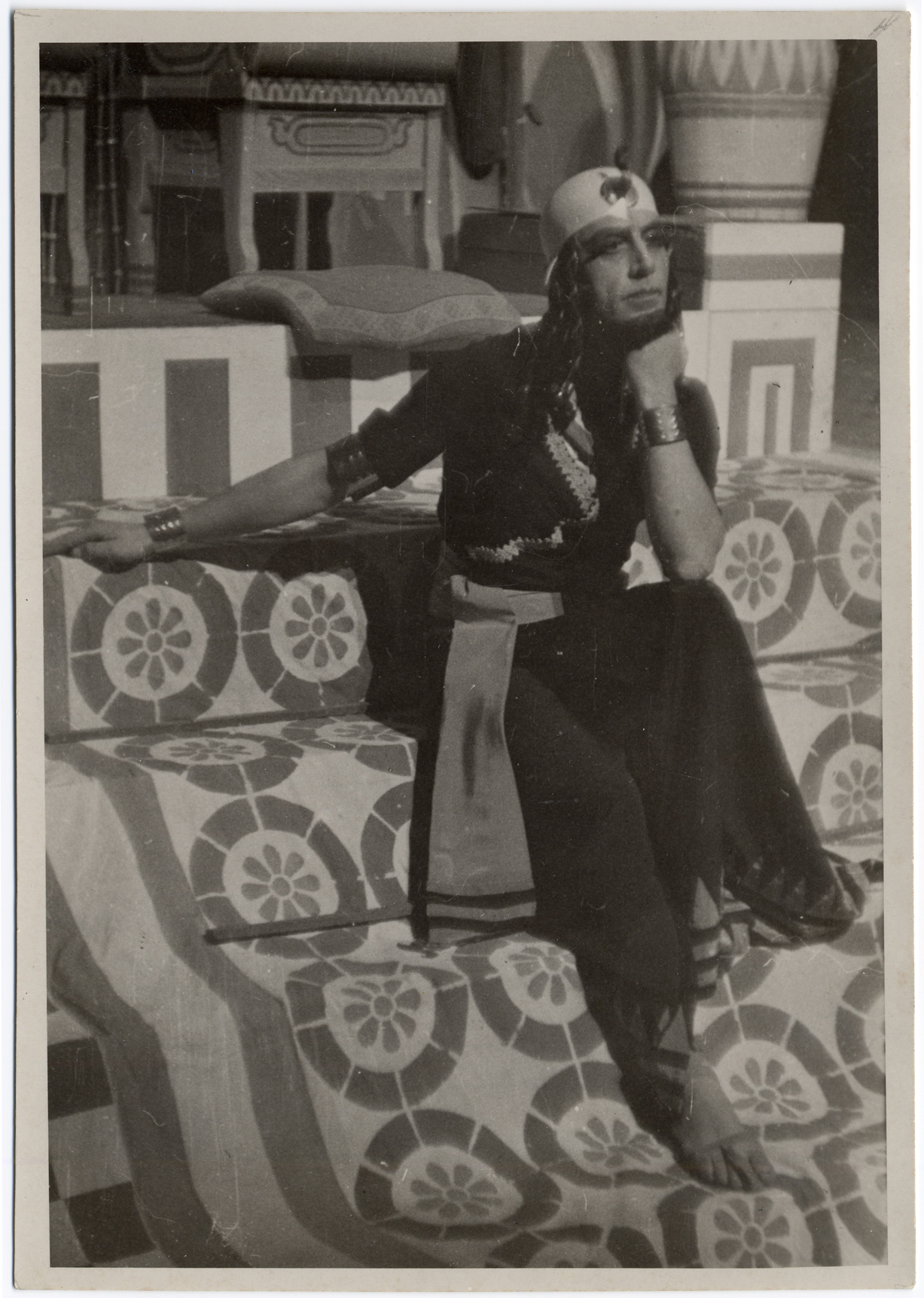

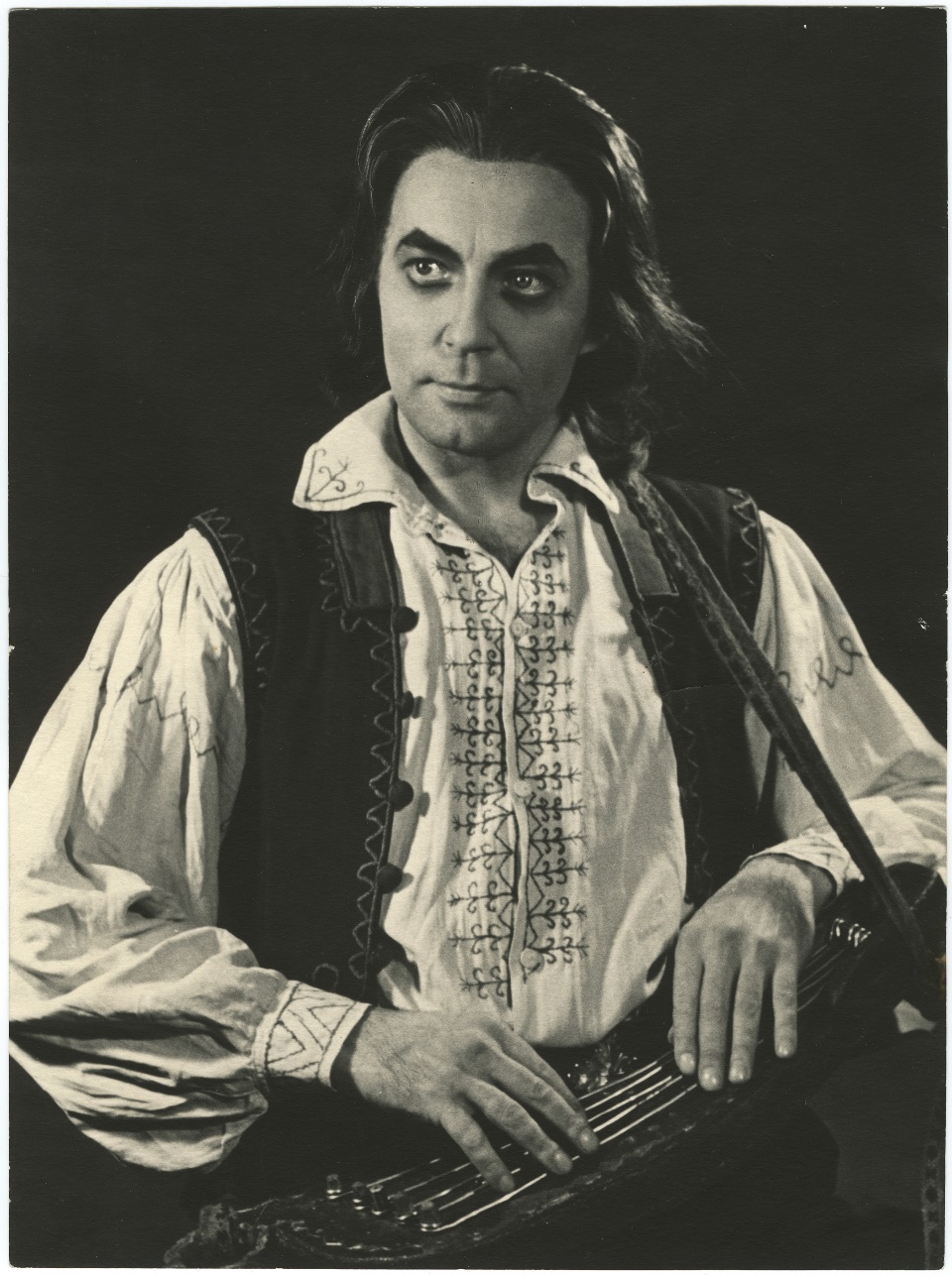

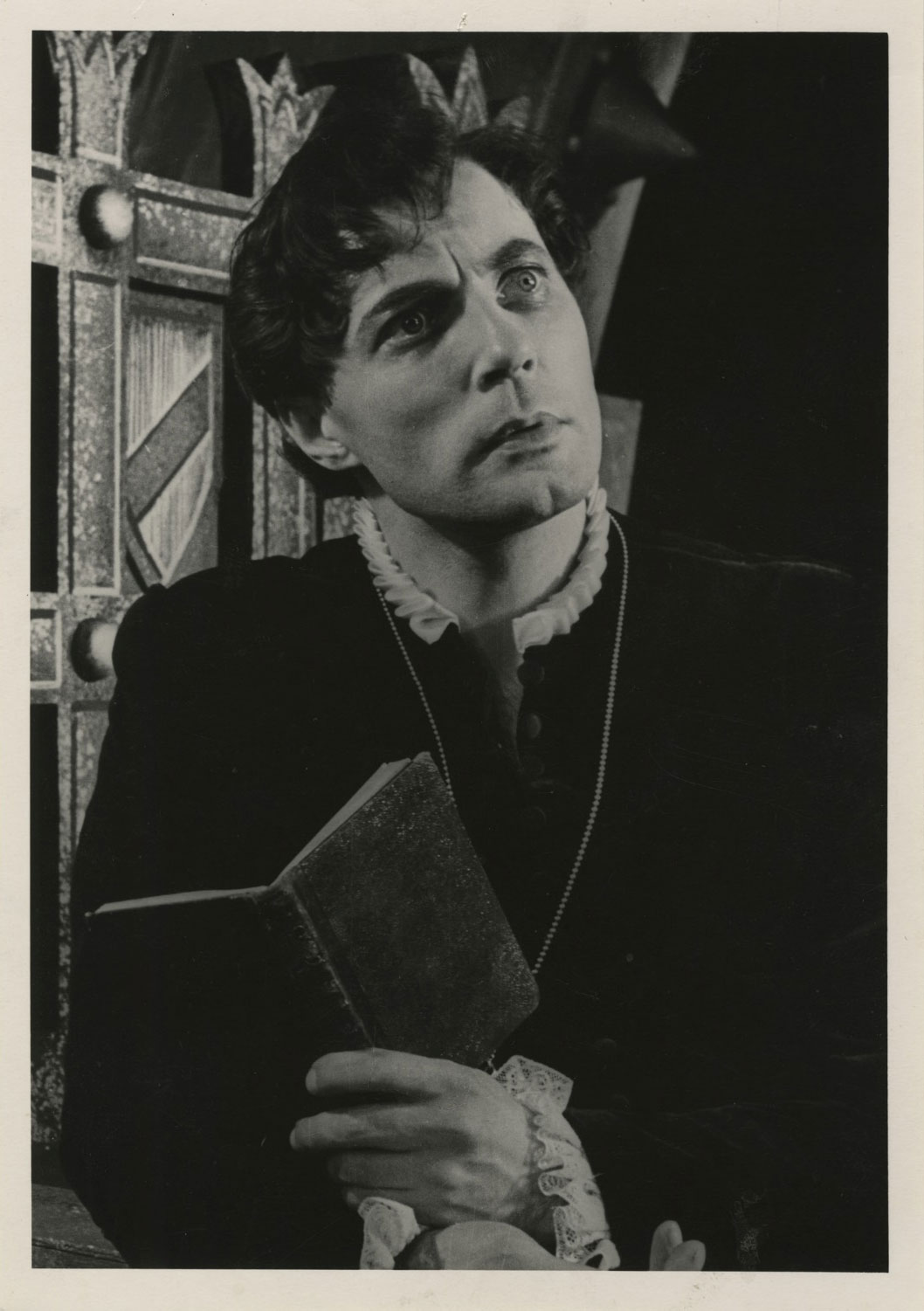

Within a few months, however, the Daile Theatre was up and running: the first play to be staged was Rainis’ “Indulis and Ārija” (Indulis un Ārija, 1920), setting the theatre’s trend to stage timeless classics that rarely had to do with current events. Smiļģis would often assume the lead roles in his own productions until 1941, and even though this approach had obvious limitations – no one was there to curb his many excesses –, this played well with the fact that he heavily increased the hitherto limited role directors had in the theatre.

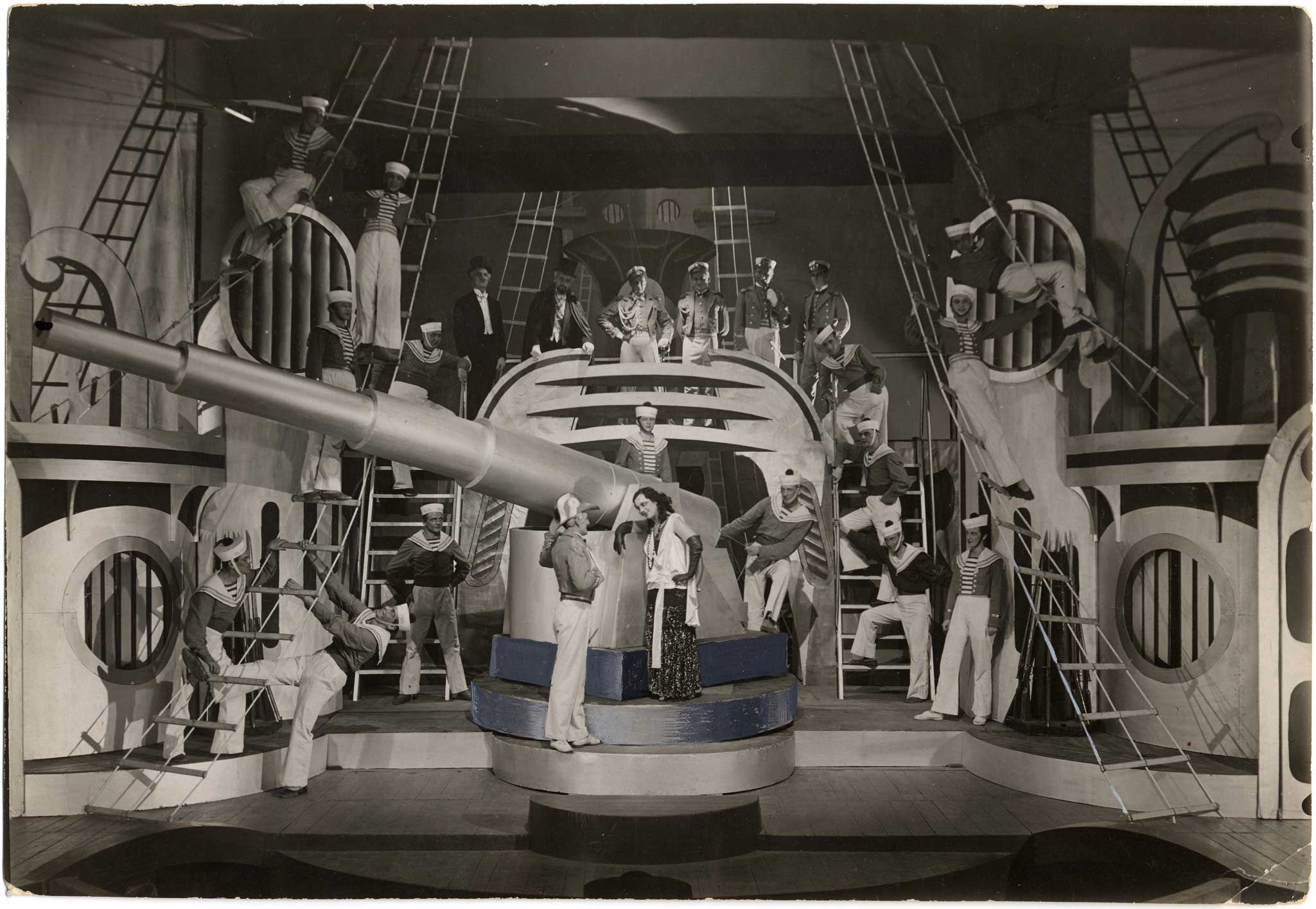

This increased control could mean many things. Smiļģis sometimes cared rather little about the actual dramatic material. The 1930 staging of Shakespeare’s “Much Ado About Nothing” was renamed “Cupid on a Dreadnought” (Amors uz drednauta), with the action taking place on a Fritz Lang-esque battleship with a glaring cannon extending over the edge of the stage.

Despite the initial difficulties, the Daile Theatre became a formidable success, introducing innovative, monumental stage designs, training actors to move and speak elegantly and making ample use of music and state-of-the-art innovations in lighting. Muncis’ modern stage designs brought the Daile Theatre international fame, as design reproductions were greeted with great enthusiasm at the 1925 Art Deco exhibition in Paris. The theatre nearly went broke from the associated costs, however.

One of Smiļģis’ major themes was power, and he was a master of subtext but not necessarily provocation. Example: he played a celebrated lead role in “Julius Caesar” (Jūlijs Cēzars, 1934) just months after Kārlis Ulmanis’ (1877–1942) authoritarian, or dictatorial coup. The years under Ulmanis were indeed marked by performances ordered from higher quarters, meant to make people proud to be Latvian, often to the point of chauvinism; but, either as a political gesture or a stroke of genius, Smiļģis managed to subvert the powers that be in a staging of Jānis Jaunsudrabiņš’ “Ralla and the Disabled Person” (Invalīds un Ralla, 1934). The staging, adored by what had remained of Latvia’s left-wing press, ended with a huge, threatening shadow of a crutch looming over the city.

“The performance was theatrically contrasted, vivid and paradoxical − and that’s why it was more effective than a pitiful realist story about another war victim,” wrote theatre critic Lilija Dzene (1929–2010).

Smiļģis’ diversions would continue under German as well as repeated Soviet occupation. As the Second World War drew to a close, with the Red Army approaching, Smiļģis staged Mārtiņš Zīverts’ “Power” (Vara, 1944). Portraying the Lithuanian king Mindaugas fighting the Tatars, its ending was readily understood by all present: “Alas, Lithuanian men! Lo, your country is burning down!”

Under the Soviets, he would extend a helping hand to the famed director Oļģerts Kroders (1921–2012), also included in the Culture Canon. A former deportee and for this very fact prevented from working in the capital, Kroders was nevertheless taken on as an assistant to Smiļģis.

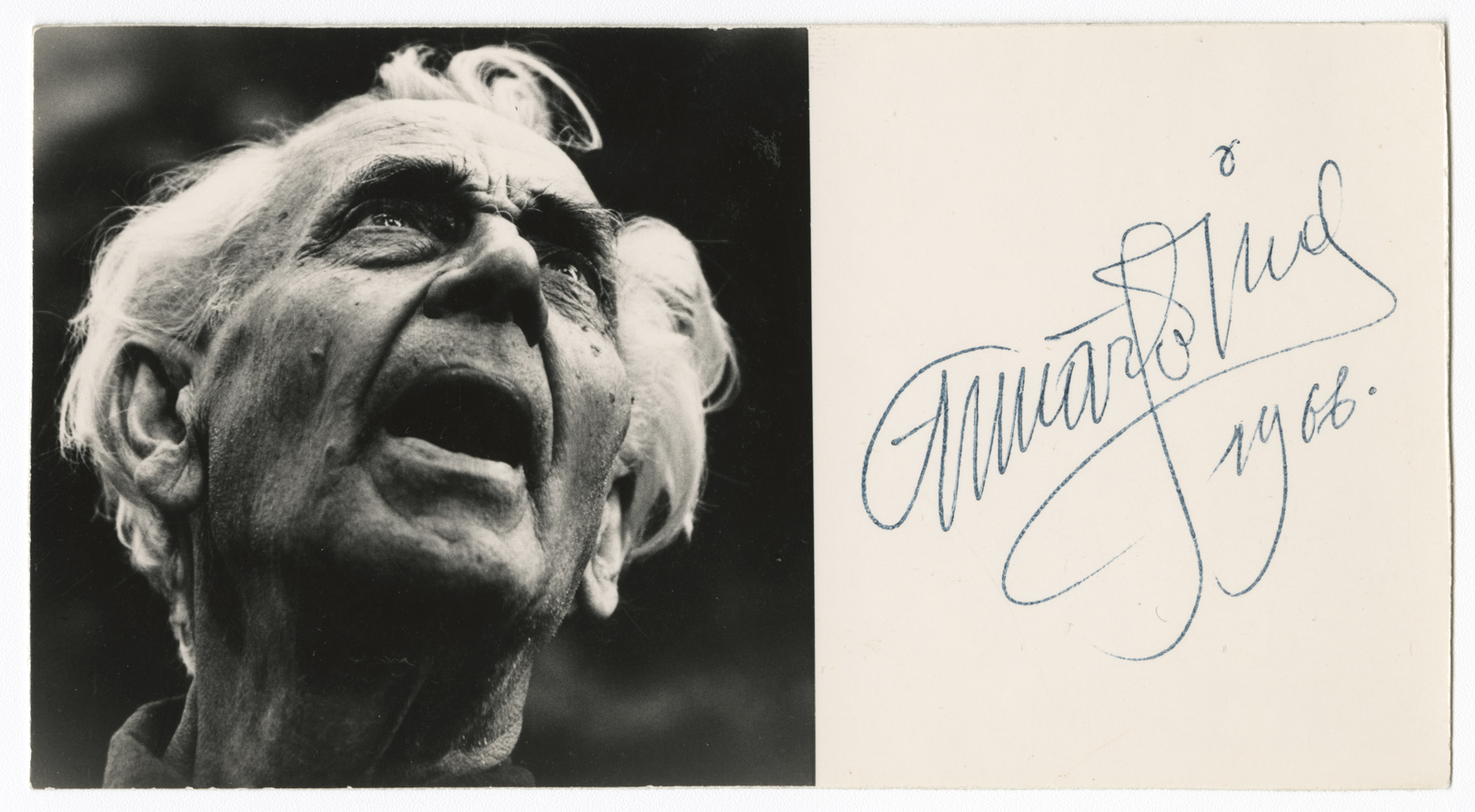

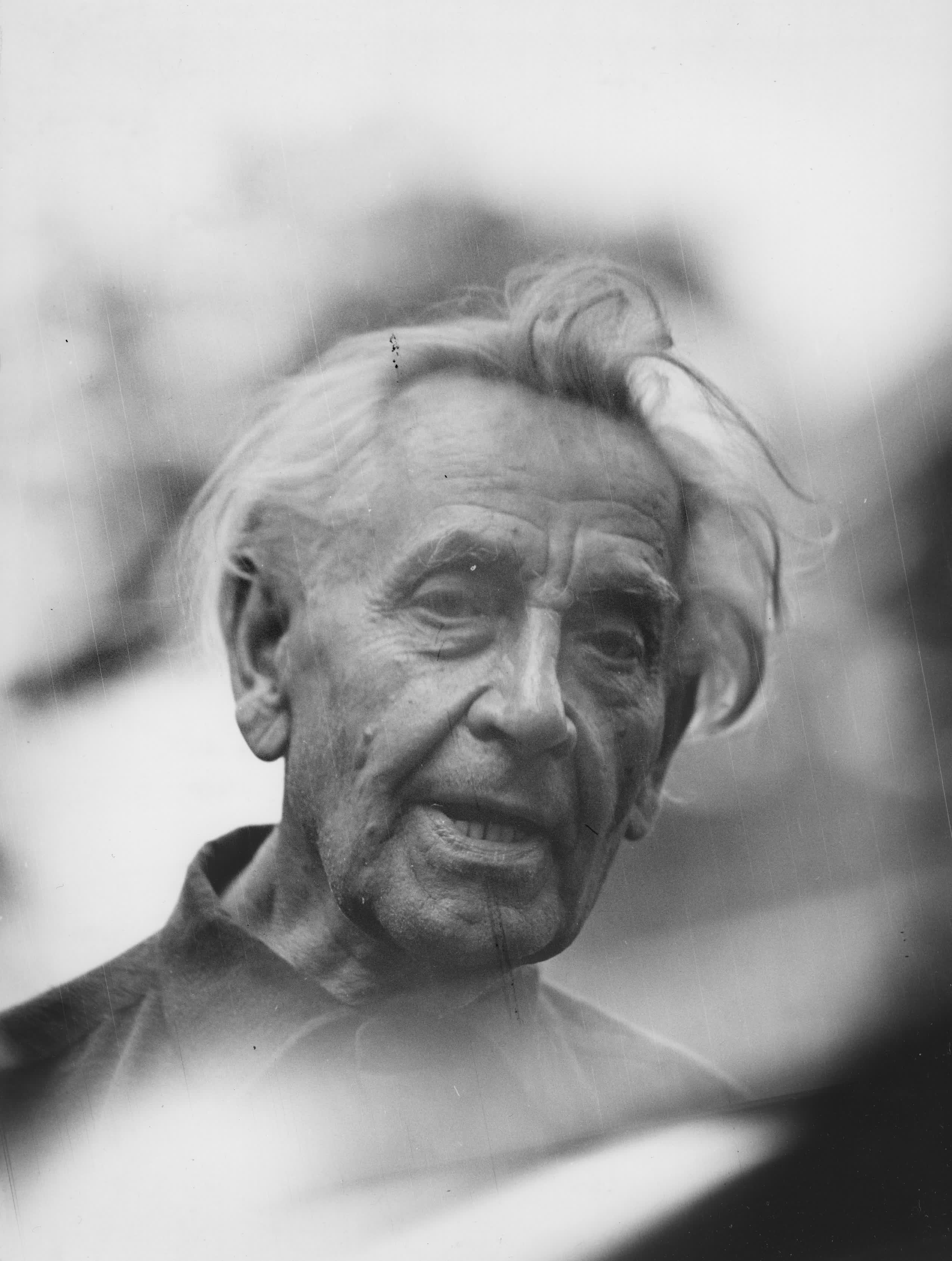

Smiļģis would continue directing until the hour of his death was very close indeed. The famous photo of him crying monumentally was taken near the end of his life, after he had been forced out of the theatre. As the story goes, photographer Gunārs Binde asked his assistant to talk with Smiļģis during the session. The assistant, in turn, provoked the great director to tears by reminding him of how he was asked to leave the theatre.

But it’s not just the photo. Smiļģis’ house is now a theatre museum; once restored, the New Riga Theatre will have a room dedicated to his heritage; and they say that the actors of the Daile Theatre are still the best in terms of athletic prowess, just as they were under Smiļģis.

Smiļģis’ life was a sustained cry, or an intense, thunderous roar, and at times we can still feel it echoing as we walk the streets of the Latvian capital.

Lauris Veips