Director Alvis Hermanis and the New Riga Theatre have been the most visible players in the Latvian theatre scene for close to thirty years. As an actor, stage designer, and director of theatre plays and operas, Hermanis has introduced audiences to ground-breaking new forms of theatre and probed the identity of the 21st century Latvia, revealing the lives of his contemporaries and bringing tradition back into the fore. Hermanis and New Riga Theatre are the world’s best-known trademarks of contemporary Latvian theatre, with Hermanis’ work and, recently, political opinions being of immediate urgency and interest to audiences across Europe.

Born into a family of a journalist and a bookstore clerk, Hermanis received a cultural upbringing, perhaps a lucky occurrence for a boy from Rīga’s Ķengarags working-class neighbourhood. As Hermanis recalls, he turned to the theatre because health problems put an end to his aspirations of becoming an ice hockey player.

His first stage experience dates back to the Riga Pantomime – included in the Latvian Cultural Canon – under Roberts Ligers (1931–2013). He studied at the Latvian State Conservatoire under Māra Ķimele (1943), whose psychological theatre is likewise included in the Canon.

Just as Latvia was to re-emerge as a republic when the Soviet Union collapsed, Hermanis spent two tumultuous journeyman years in New York, working odd jobs and coming close to the brink when he spent a winter in an unheated slum in South Bronx. Hermanis returned to Latvia a new man. “Until then, I was shaped by the circumstances, but after coming back it was I who shaped them,” he writes in his diary.

The New Riga Theatre was established in 1992, after Adolf Shapiro’s Riga Youth Theatre was disbanded. It started running Hermanis’ productions in 1993 under Juris Rijnieks (1958), whom Hermanis replaced as artistic director in 1997, setting up his own permanent troupe. His productions of the 1990s made use of diverse, original and often provocative ideas, making pastiches and bringing together characteristics of different eras and cultures. Even though his work attracted professional attention, it was often criticised for intellectual detachment and postmodern irony.

The public really warmed up to Hermanis when he produced a psychologically nuanced rendering of “The Promise” (Mans nabaga Marats, 1997). “The Promise” follows a love triangle in the years after the Second World War in Russia. It captured viewers’ hearts to such an extent that its stage run lasted 14 years. During the time, lead actors Baiba Broka (1973), Andris Keišs (1974) and Vilis Daudziņš (1970) grew from young and talented actors into master performers, while Hermanis and the New Riga Theatre gained a cult following in Latvia and reached audiences abroad.

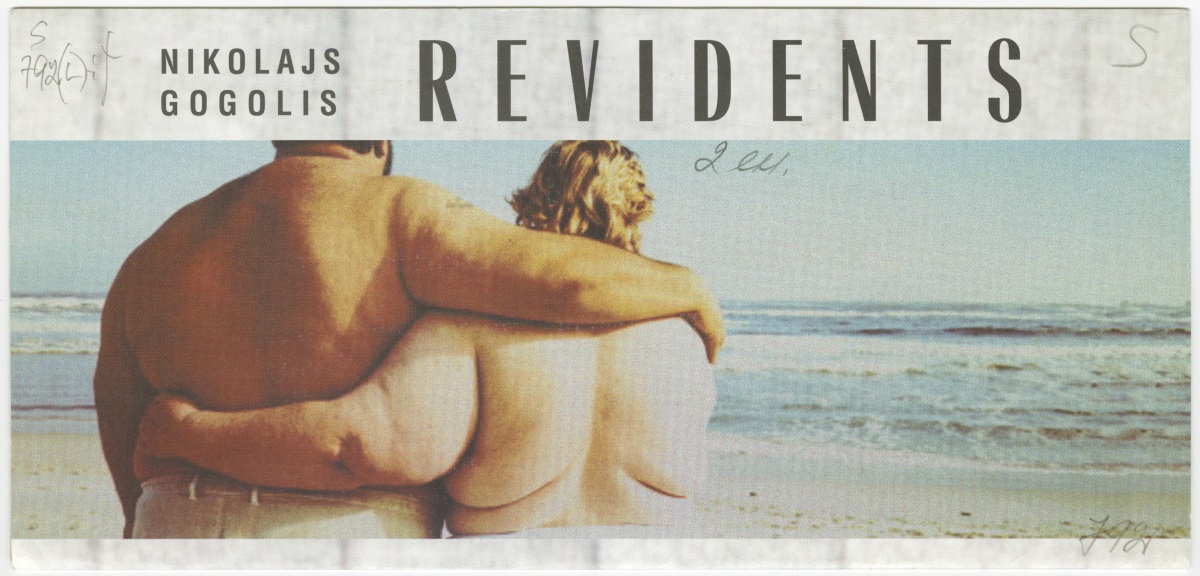

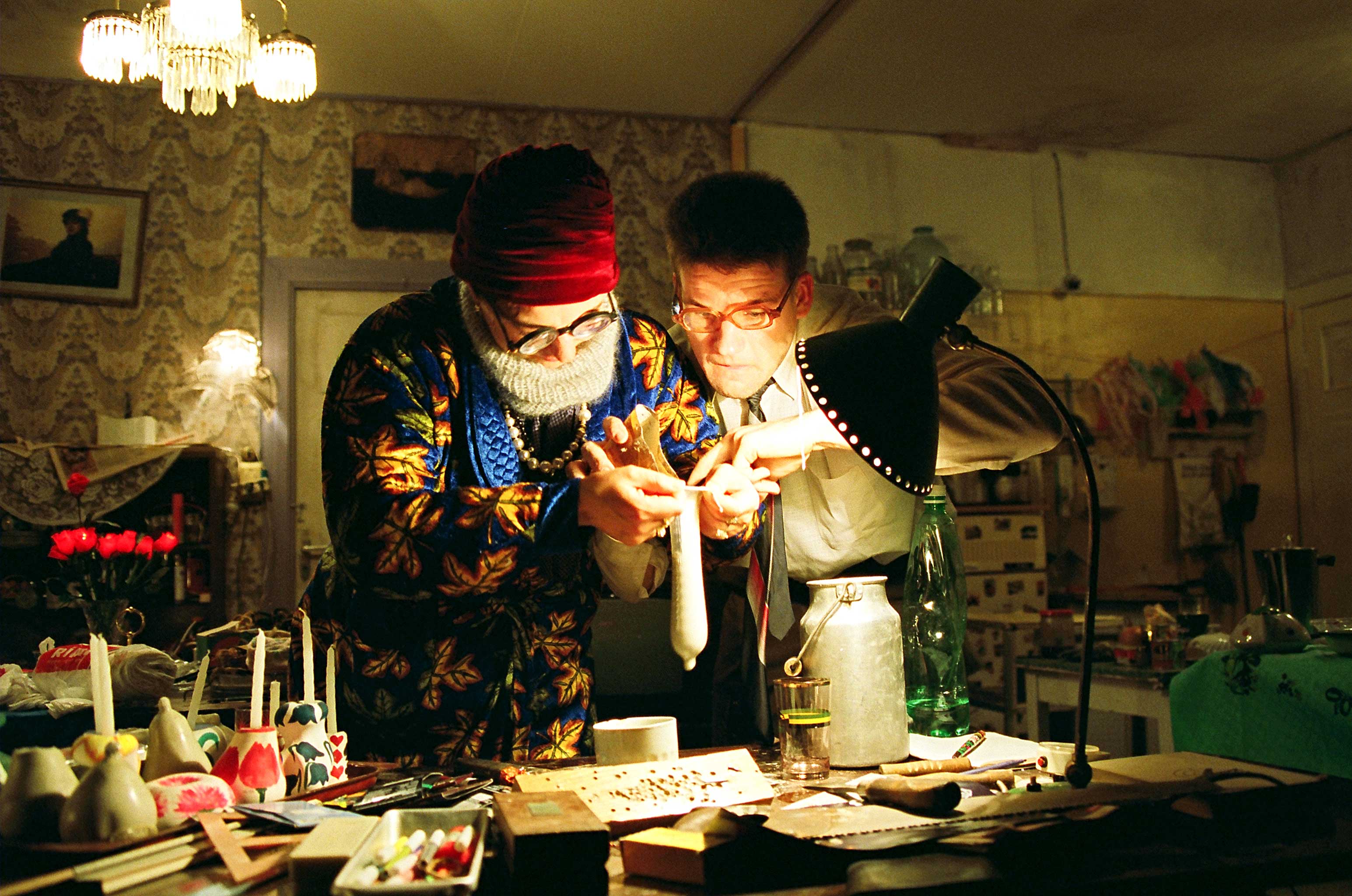

The first international hit for Hermanis and the New Riga Theatre was a rendition of Nikolai Gogol’s “The Government Inspector” (Revidents, 2002). Hermanis shifted the play’s action from a 19th century Russian governorate to a provincial canteen in the Soviet era. In a vividly grotesque staging, actors’ figures were refitted with fat wipes made of foam rubber, objectifying the characters’ sluggish state of mind and soul. Actors played their own musical accompaniment with the aid of kitchen utensils. Adding to the confusion were chickens on stage and a smell of cooked onions permeating the room.

The public loved it; and critics were exalted. Normunds Naumanis (1962–2014) singled it out as a milestone in Latvia’s theatre history: “Finally, for the first time ever, this production is one about which we can say: world class art… an enormous leap in the director’s professional development.”

Hermanis’ own assessment is more understated. He says that with “The Government Inspector”, he “understood that being a snob, of course, may be very pleasant, but in theatre it is best to talk of human matters, and simple and strong themes”.

In another creative leap, Hermanis shook up the way New Riga Theatre makes productions with “The Long Life” (Garā dzīve, 2003). Hermanis memorably said that the life of every Latvian resident has more drama than the works of Shakespeare put together. From here on out, actors became co-authors, identifying and producing much of the material collectively.

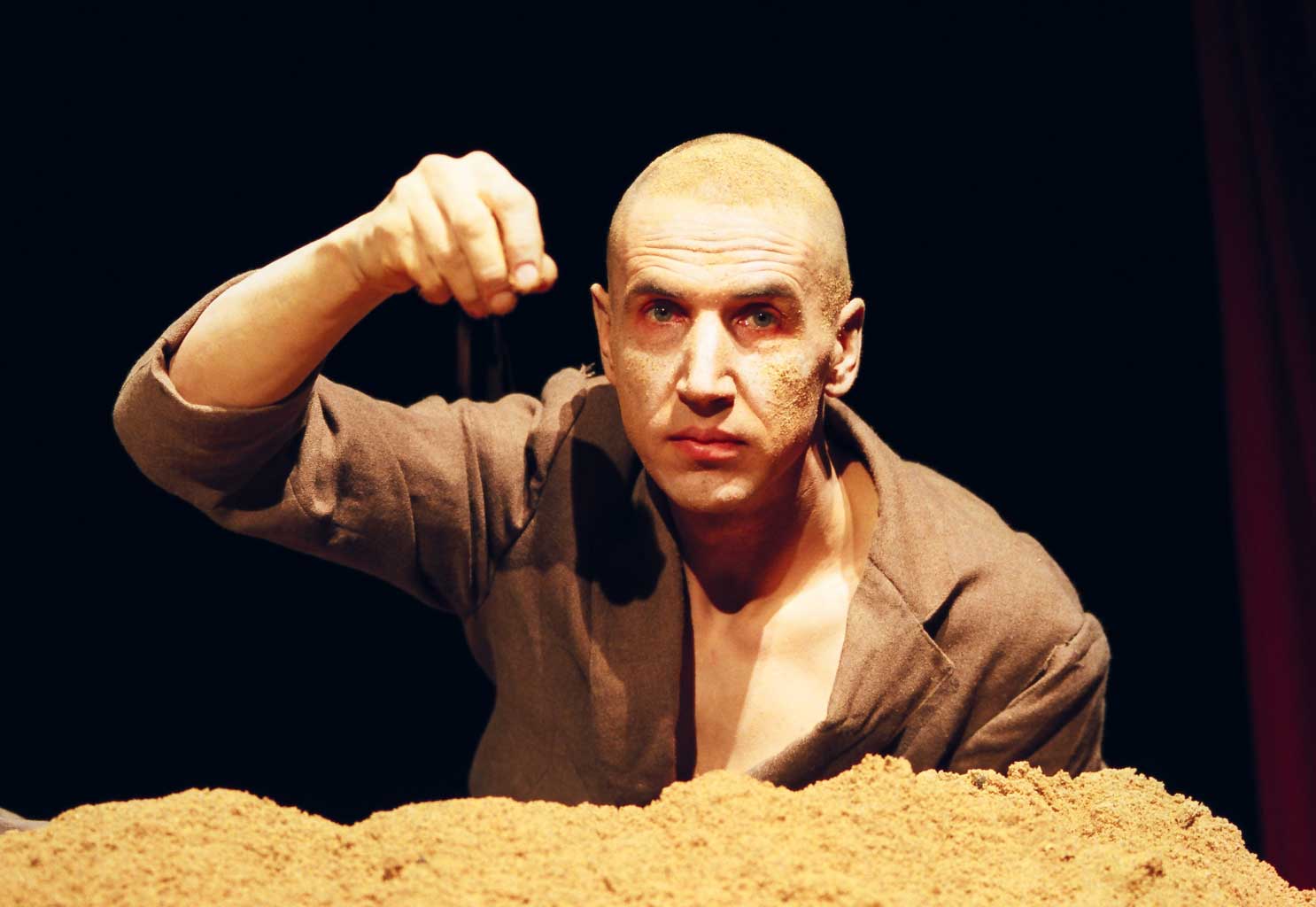

A daring experiment in theatrical narrative, “The Long Life” portrays, without words, a day in the life of the residents in a communal apartment, all very old people. Actors Baiba Broka, Guna Zariņa (1972), Vilis Daudziņš, Ģirts Krūmiņš (1965), and Kaspars Znotiņš (1975) were only in their thirties when it was first staged but managed to precisely and touchingly depict the way old people think and feel, and act. It won worldwide recognition: audiences in a total of 35 countries have connected with the mutely told story of feeble and weary Latvian pensioners, a story which may point to the great silence that awaits us all.

Hermanis returned to text, in narrative form, with “Latvian Stories” (Latviešu stāsti, 2004). For this production, actors were instructed to go out and get to know different Latvian people. Actors learned about the everyday lives and fates of regular Latvians and told their stories from the theatre stage. This “human interest” trend continued in “Latvian Love” (Latviešu mīlestība, 2006), “The Sounds of Silence” (Klusuma skaņas, 2007), “Marta from the Blue Hill” (Zilākalna Marta, 2009), “Commemorating the Dead” (Kapusvētki, 2010) and “Black Milk” (Melnais piens, 2010).

In several productions, Hermanis has used the traditional heritage of Latvia, using patterns from the Belt of Lielvārde in “Further” (Tālāk, 2004) and addressing commemorative cemetery rituals and grave tending in “Commemorating the Dead”. The production “Ziedonis and the Universe” (Ziedonis un Visums, 2010) is dedicated to the poet Imants Ziedonis (1933−2013), also included in the Latvian Culture Canon. Actor Kaspars Znotiņš displayed excellent performance as the poet, particularly as concerns vocal mimicry. This artistic period of Hermanis can be considered to be a great investment into researching and popularising matters pertaining to the identity of modern Latvia.

Hermanis has also confronted the subject of 20th century totalitarian regimes with an adaptation of Vladimir Sorokin’s novel “Ice”, staged under the title, “Ice. Collective Book Reading with the Help of Imagination in Rīga” (Ledus. Kolektīva grāmatas lasīšana ar iztēles palīdzību Rīgā, 2005) and Tatyana Tolstaya’s “Sonya” (Soņa, 2007).

Meanwhile “Oblomov” (Oblomovs, 2011), “Onegin. Commentaries” (Oņegins. Komentāri, 2012), “Brodsky/Baryshnikov” (Brodskis/Barišņikovs, 2015) and “Submission” (Pakļaušanās, 2016) have seen Hermanis tackle questions related to the resignation of Western culture and civilisation. “Brodsky/Baryshnikov”, a one-man-act, features Rīga-born ballet luminary Mikhail Baryshnikov (1948) performing poems of his long-time friend Joseph Brodsky (1940−1996). It has toured around the globe to positive acclaim. While “Submission”, an adaptation of the eponymous Michel Houellebecq novel, has seen Hermanis further cement his provocative reputation after he broke with Hamburg’s Thalia Theatre over the theatre’s refugee policies in 2016.

Hermanis and his productions at New Riga have received numerous international accolades, including the prestigious Europe Theatre Prize for “New Theatrical Realities” (2007). Since 2005, Hermanis has been actively staging operas and plays in different German, Russian, Swiss, Italian, Austrian, Belgium and French theatre houses.

The New Riga Theatre building on 25 Lāčplēša Street has witnessed some of the greatest events and people of Latvian theatre history, included in the Culture Canon, such as Aleksis Mierlauks’ 1911 adaptation of Rainis’ play “Fire and Night”, Eduards Smiļģis’ Dailes Theatre, Pēteris Pētersons’ Poetry Theatre, Adolf Shapiro’s Youth Theatre, and Henrik Ibsen’s “Brand”, as directed by Arnolds Liniņš (1975). The building’s big history is shown due respect as it’s being refitted for more space, preserving Gunārs Binde’s (1933) big and expressive photo portrait of Eduards Smiļģis on the building’s side; it’s also planned to name one of the stages after Smiļģis.

Most recently, Hermanis has returned his sights to the local scene. He broke with a part of New Riga’s permanent troupe and will be training new actors at the Latvian Academy of Culture starting with the 2018 academic year.

Hermanis’ political opinions continue to have an acute urgency, as evidenced by the fact that he was named the country’s most influential thinker in online surveys by the Satori magazine in 2013 and 2016.

Lauris Veips