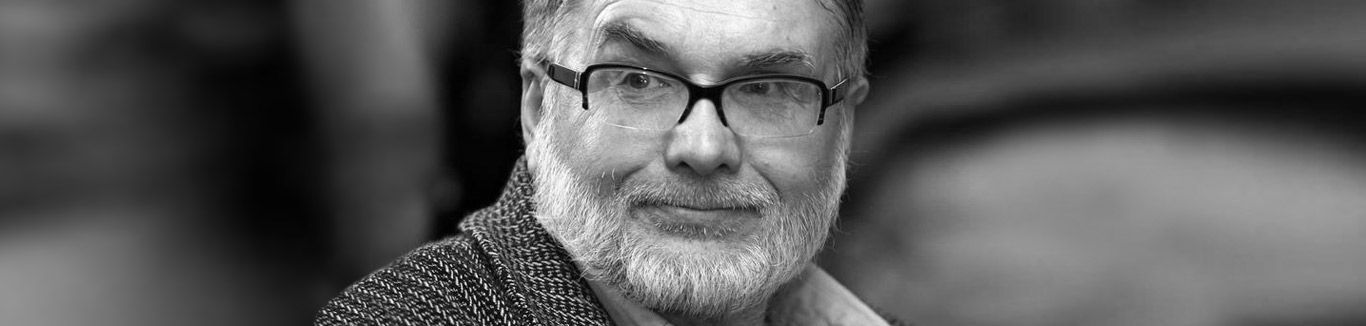

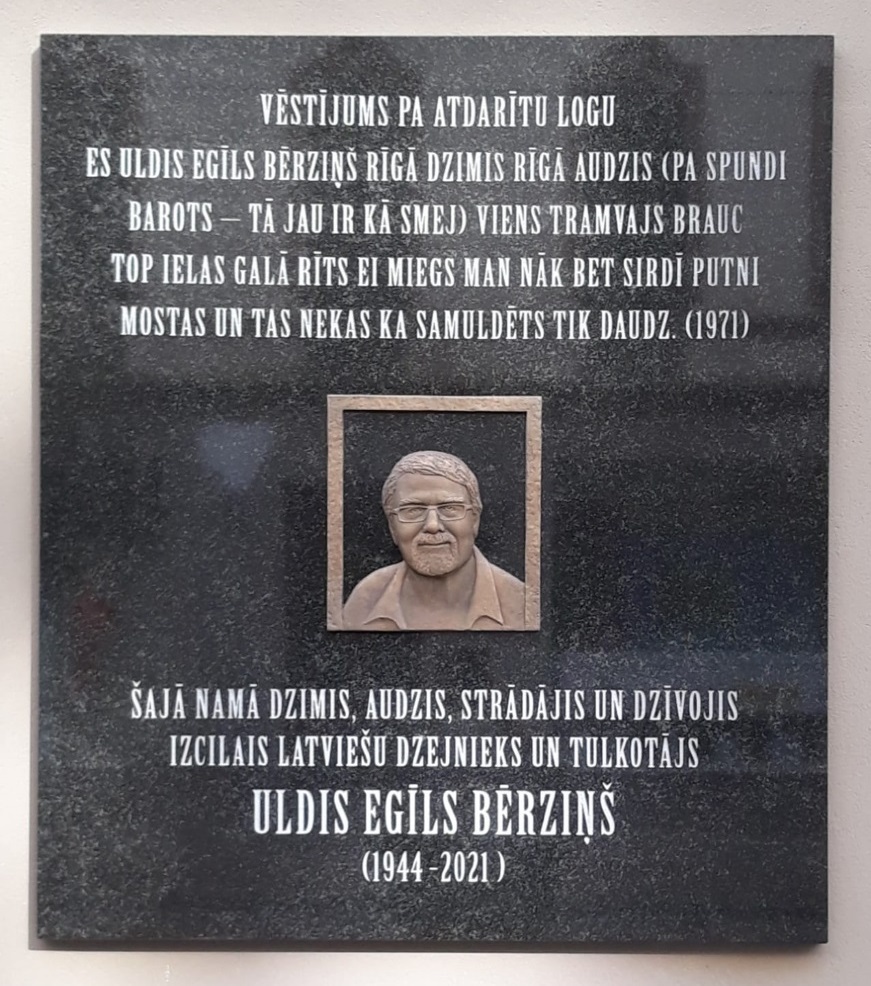

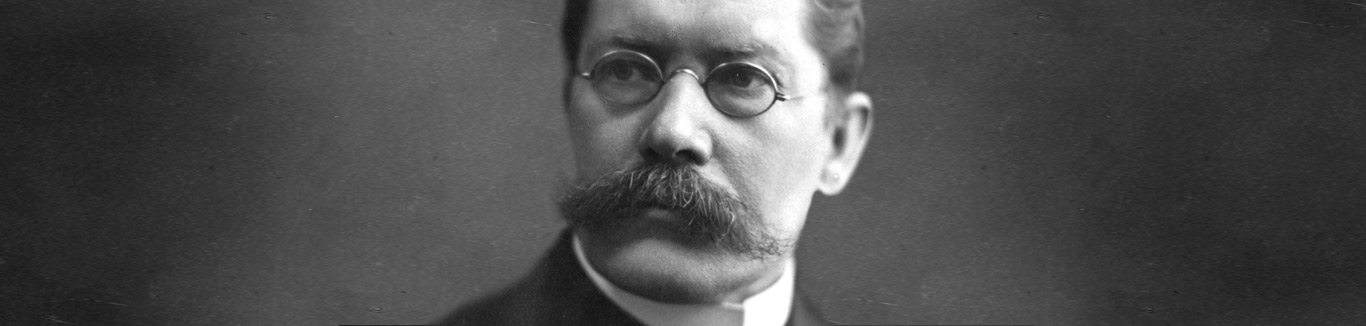

Poetry by Poet Uldis Bērziņš (1944–2021)

To illustrate Uldis Bērziņš’ (1944) significance in Latvian letters, a good start would be noting that he has translated such diverse works as the Quran, the Icelandic Eddas, as well as parts of the Old Testament into Latvian. Bērziņš’ own poetic output, meanwhile, is instantly recognizable but not easily described. In addition to a reverence for the sacred and finding its presence in the high and the low orders of human experience, it is characterized by a focus on language as a sovereign phenomenon – indeed, Bērziņš repeatedly envisions language as something of a primordial, life-giving substance.

Guntis Berelis on Uldis Bērziņš in the Latvian Culture Canon, 2008. (in Latvian)

Autograph of the poem "Klāt brienu Māras zābakos…" by Uldis Bērziņš. 1972. National Library of Latvia, Collection of Rare Books and Manuscripts. (in Latvian)

Autograph of the poem "Plauc, atlidos Maija un lapenīte…" by Uldis Bērziņš. 1974. National Library of Latvia, Collection of Rare Books and Manuscripts. (in Latvian)

Autograph of the poem "Lejiet to duļķaino sauli, grieziet to maizi…" by Uldis Bērziņš. 1975. National Library of Latvia, Collection of Rare Books and Manuscripts. (in Latvian)

Autograph of the poem "Pēterbalādes. 1. Balāde par gaiļiem" from the series "Čaka pilsēta" by Uldis Bērziņš. National Library of Latvia, Collection of Rare Books and Manuscripts. (in Latvian)

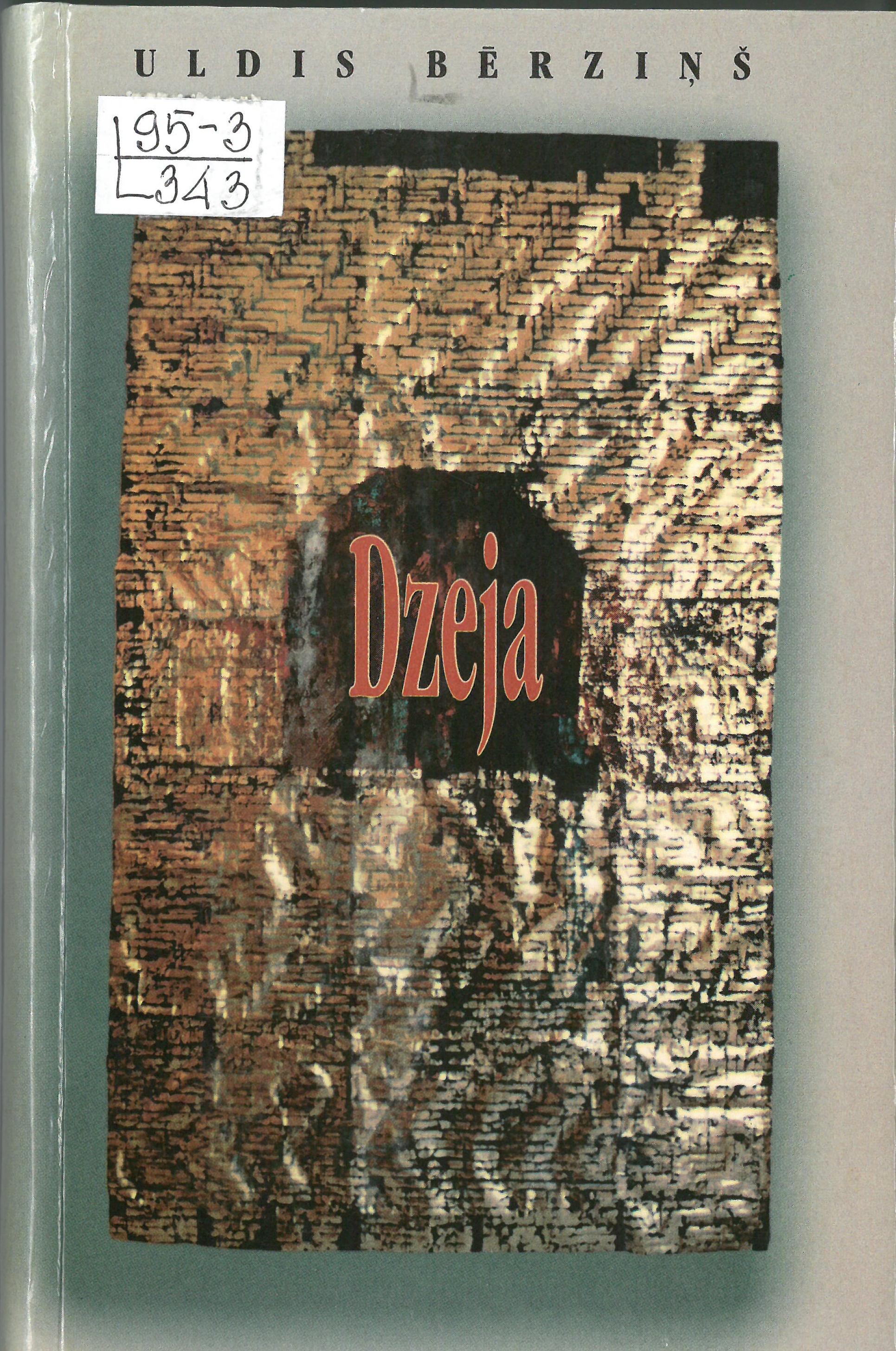

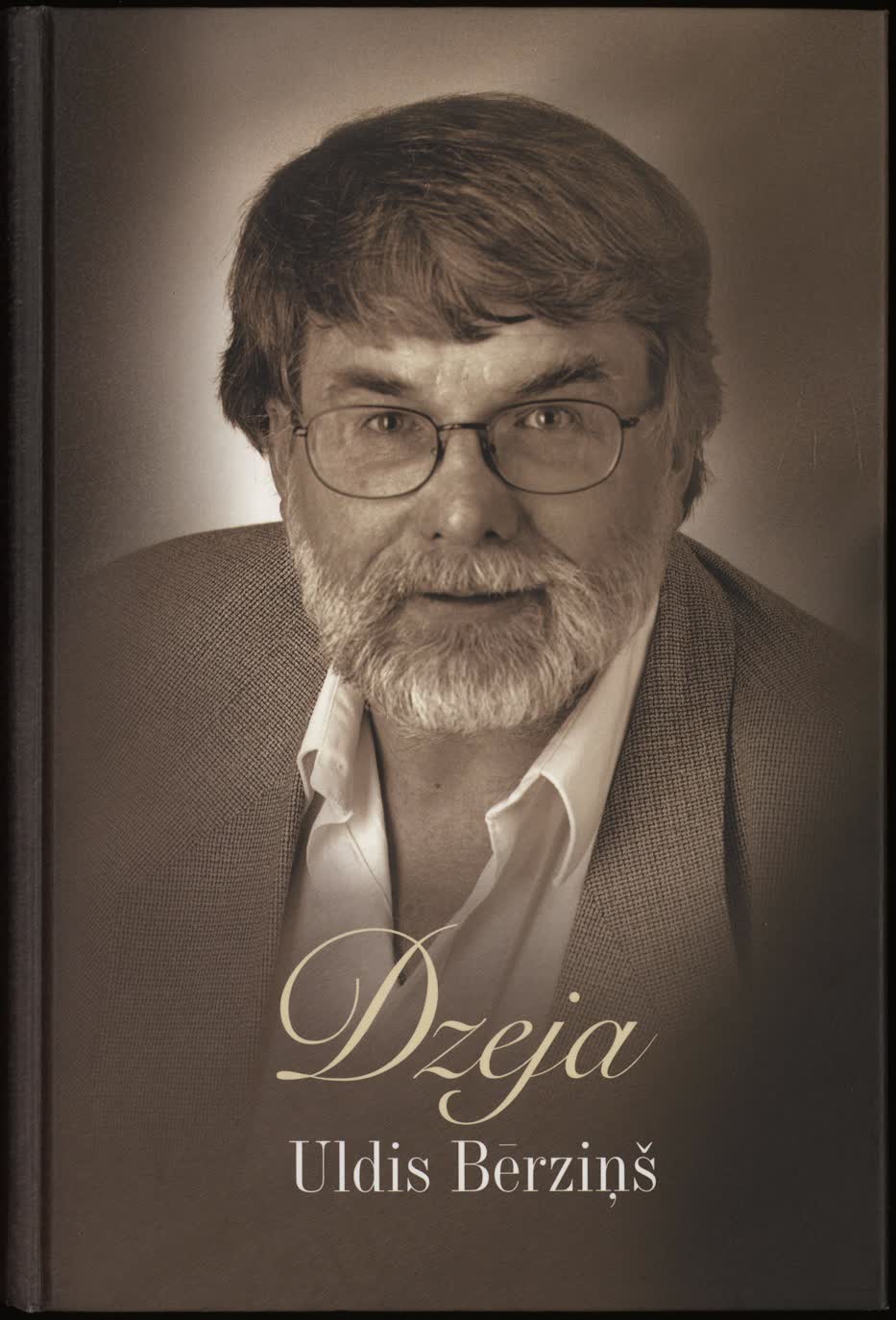

Fragments from "Dzeja" (Poetry) by Uldis Bērziņš, 2004. (in Latvian)

Guntis Berelis on Uldis Bērziņš in the Latvian Culture Canon, 2008.

Berelis, G. (1999). Arhaisti un modernizētāji: Ulda Bērziņa, Jura Kunnosa un Pētera Brūvera dzeja. No: G. Berelis. Latviešu literatūras vēsture (256.-259. lpp.). Rīga: Zvaigzne.

Čaklā, Inta. (2013). Minūtes, gadi un citi Ulda Bērziņa dzejas laiki. No: Inta Čaklā. Kas dzīvo vārdos: raksti par literatūru (175.-184. lpp.). Rīga: LU Literatūras, folkloras un mākslas institūts. Kritikas bibliotēka.

Čaklā, Inta. (2013). Ulda Bērziņa kosmogonija: [par Ulda Bērziņa dzeju krāj. „Dzeja” (Rīga: Atēna, 2004)]. No: Inta Čaklā. Kas dzīvo vārdos: raksti par literatūru (117.-119. lpp.). Rīga: LU Literatūras, folkloras un mākslas institūts. Kritikas bibliotēka.

Kursīte, Janīna. (1994). Uldis Bērziņš. No: Latviešu rakstnieku portreti: 70.-80. gadi (26.-32., 159.-185. lpp.). Rīga: Zinātne.

Salējs, Māris. (2007). Uldis Bērziņš. No: Latviešu dzejnieku portreti: rakstu krājums (159.-185. lpp.). Rīga: Zinātne.

Salējs, Māris. (2011). Uldis Bērziņš: dzīve un laiktelpas poētika. Rīga: Latvijas Universitātes Literatūras, folkloras un mākslas institūts. Studia humanitarica.

Vērdiņš, Kārlis. (2011). Uldis Bērziņš un citi 70. gadu dzejnieki. No: K. Vērdiņš. Bastarda forma: latviešu dzejprozas vēsture, latviešu dzejprozas antol. (199.- 203.[213] lpp.). Rīga: LU. Lit., folkloras un mākslas inst.