The greatest Latvian geographical treasure is its seacoast – a location that gives colour to the whole country. Connection with the sea, where inland roads meet sea roads, is the nation’s historical keystone. Geographer Jānis Rutkis says that “the coast is all land’s front [is the frontal side of the country] that is pointed towards the west and north-west of Europe.”

The seacoast is Latvia’s only natural border, where, from Nida to Ainaži, in almost 500 km long line counteracts various landscapes of struggle and cooperation between sea and land. They are saturated with historical sites, ethnical culture spaces, coastal lifestyle heritage, symbolic significations and unique nature values, and the footprints of Latvia’s difficult history of the 20th century. This diverse and dynamic area has white sand beaches with dune forts, pebble and rocky beaches, ports and piers, villages enclosed by dunes, pine tree forests with storm-bent branches and trunks, steep bluffs and sandstone cliffs, coastal meadows, river mouths and large river deltas, bigger and smaller towns. It is a landscape, where the dynamics of nature is in their strongest version – here are the most restless waters, coasts subjected to the rhythm of the sea, winds and storms. It is a landscape with a horizon, a landscape, which always astonishes with its views, the most remarkable Latvia’s space of vastness and farness.

The landscape of coastal region, which mostly is flat and gently sloping towards the sea, is made up by two different lanes – the diverse coast and its uniform backside. The coast is the active space of this plain, there are towns, villages and farmsteads. The backside of the coast, that stretches inland, can be called as the coastal plain’s passive space, on sandy sediments, it is made up of forests and marshes. The coastal plains’ inland border coincide with the former Baltic Ice Lake coastline, from where the glacial melting waters had retreated during the glacier’s withdrawal and land’s isostatic uplifting. Therefore, in the topsoil where the former seabed was, are mostly marine sediments – sand, reworked from the underlying bedrock, which in many parts of the coastal region is drifted into dunes.

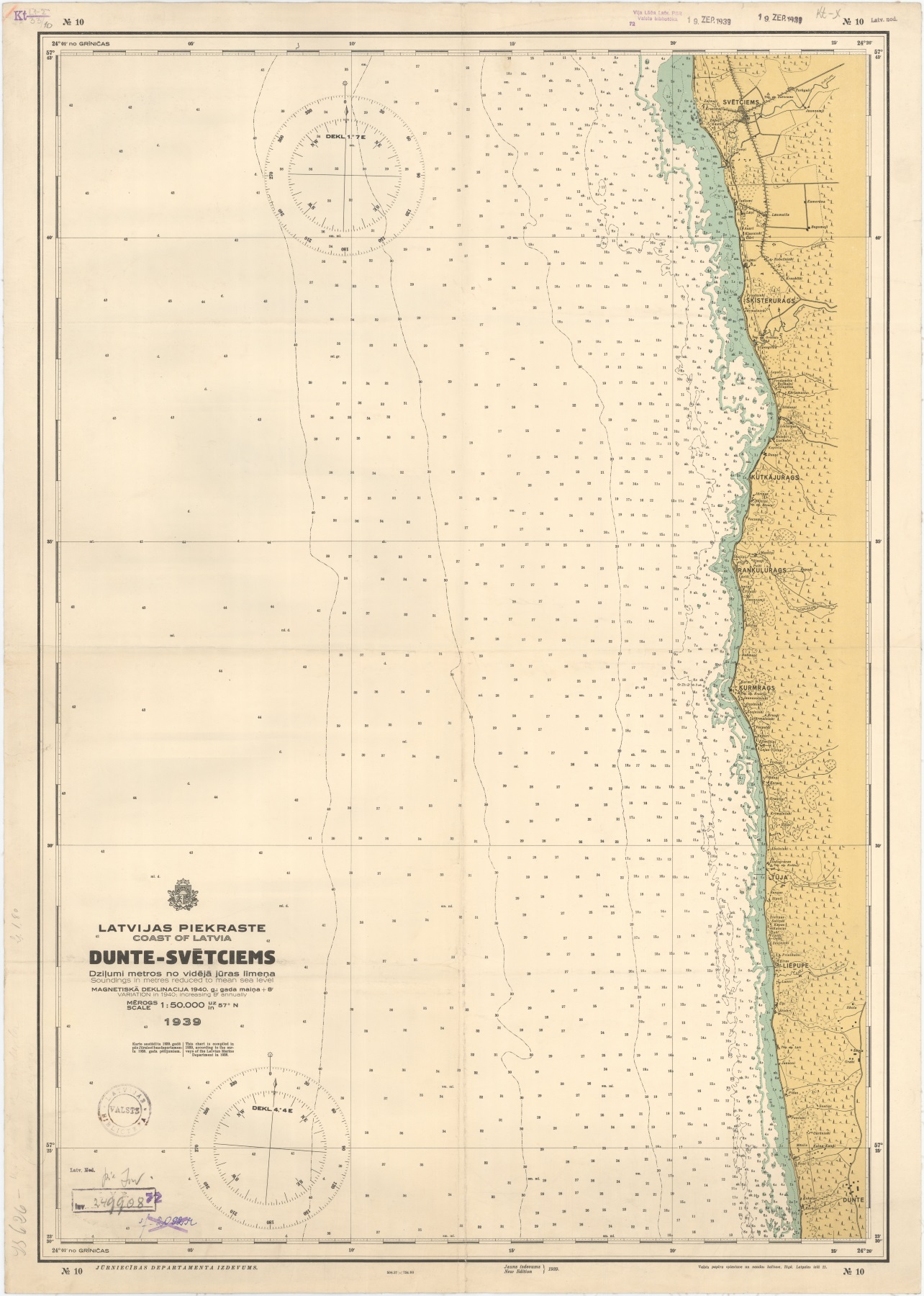

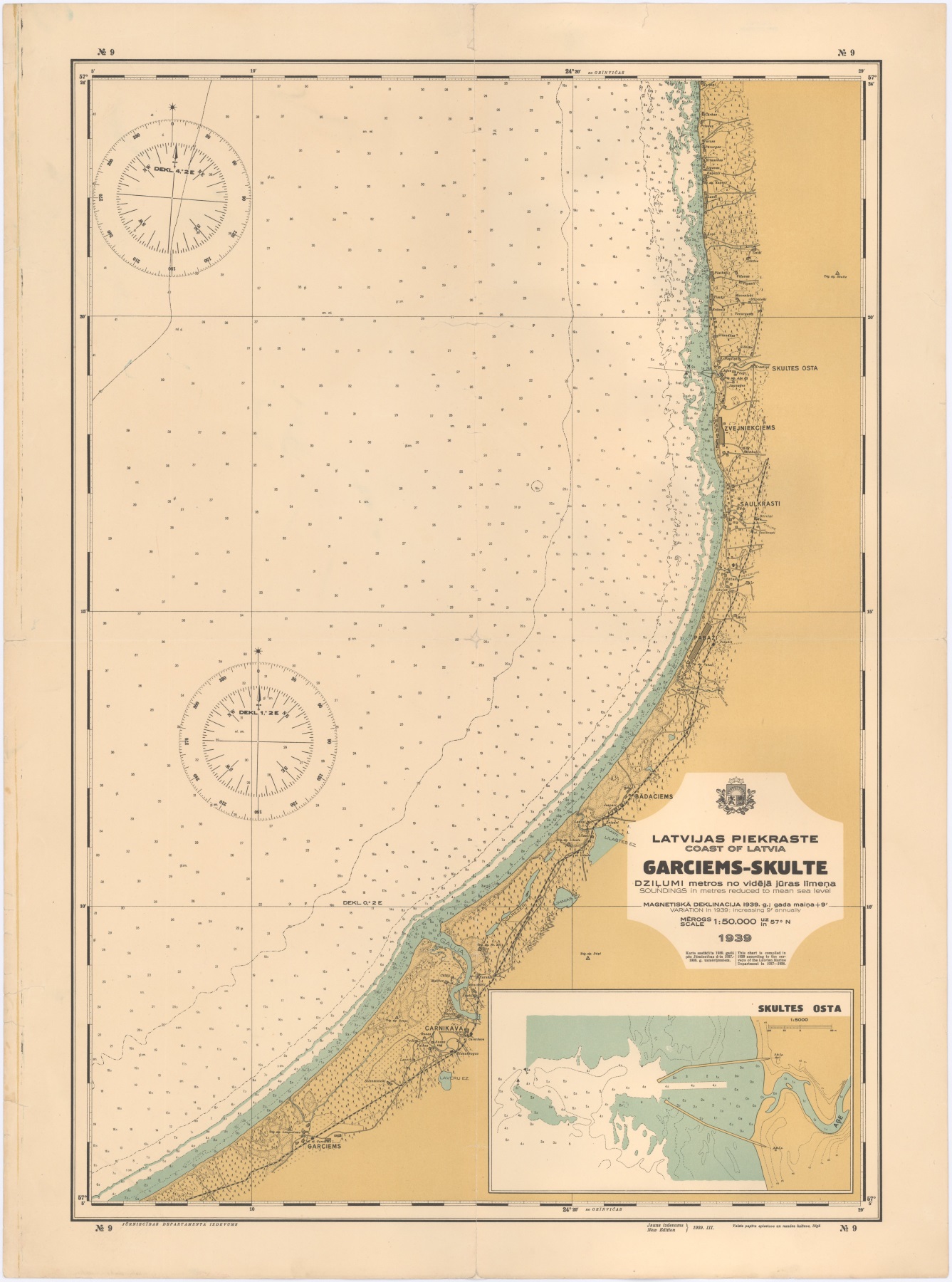

The landscape of seacoast is made up from diverse and dynamic nature forms of the sea-land interaction, although the coastline itself in Latvia is quite straight, and only in a handful of places it has distinct curvatures – horns (rags) (e. g., Akmeņrags, Mērsrags, Ķurmrags). The Latvia’s coast has wave-dominated beaches, that are flooded during storms, but when the sea is calm, the wind blows the sand to the coastal dunes. In large parts the coast is made up of fine sand, often forming smooth beaches, the so-called “white beaches”. In the beaches of Ainaži, Ķurmrags, Liepupe, Mērsrags, Roja, Užava, Sārnate, and Pape there are sections of bigger and smaller stones or pebble beaches. The picturesque seaside with boulders, that are leftovers of glacial end-moraines, can be found in Kaltene, Engure, but especially in Vidzeme coast (from Meleki to Tūja), and in some sections it is accompanied by seashore bluffs with Devonian sandstone outcrops, with the most impressive being the Sarkanās (Red) Cliffs or Veczemju Cliffs with wave-carved grottos and caves. South from Ainaži the beache is overgrown with grass – it is Latvia’s unique coastal meadows (Randu pļavas), which consist of the mosaic of reeds, coastal meadows, lagoons, sludgy small lakes and sandbanks.

An integral part of the coastal region is the dune landscape – sand hills created by sea breakers and wind that takes various shapes, often in multiple parallel strips. In some places, especially south from Liepāja and around large river mouths in the Gulf of Rīga, the dunes reach considerable heights. Nowadays these dune ridges have abated, and they are covered with pine forests, but in the beginning of 20th century they moved a lot and buried coastal forests, meadows and villages. The dynamic landscape of sand manifests in the coastline in various sand banks and shoals, from which the most impressive is Cape Kolka or Kolkas rags (Kolka Horn), which prolongs far in the sea as a sandbank. This is one of the Latvia’s iconic landscapes, a place where two seas meet – the Great See (Dižjūra, the Baltic sea) and the Small Sea (Mazjūra, the Gulf of Rīga). In the western coast of Kurzeme, especially between Jūrkalne and Pāvilosta, a picturesque seashore bluff landscape has formed – high sea abrasion slope, which discloses the blue and grey moraine layers of Kurzeme ice formation.

The coastal landscape is diverse also due to its littoral waters: river mouths and their dynamic beds, big river deltas, which over time have been adjusted for ports. Natural interaction between the sea and large river today can be seen only with the Gauja river – one of the most beautiful river deltas in Latvia. Also, the shallow coastal lakes, that are important nesting and migration territories for birds (wetlands of international importance), is an essential part of the landscape. These are the ancient sea lagoons that have parted from the sea with sandbanks or dune ridges (for example, Lake Pape, Lake Engure, Lake Kaņieris) during the regression stages in the Baltic Sea history, or ancient river bed relics (for instance, Lake Babīte and Lake Jugla).

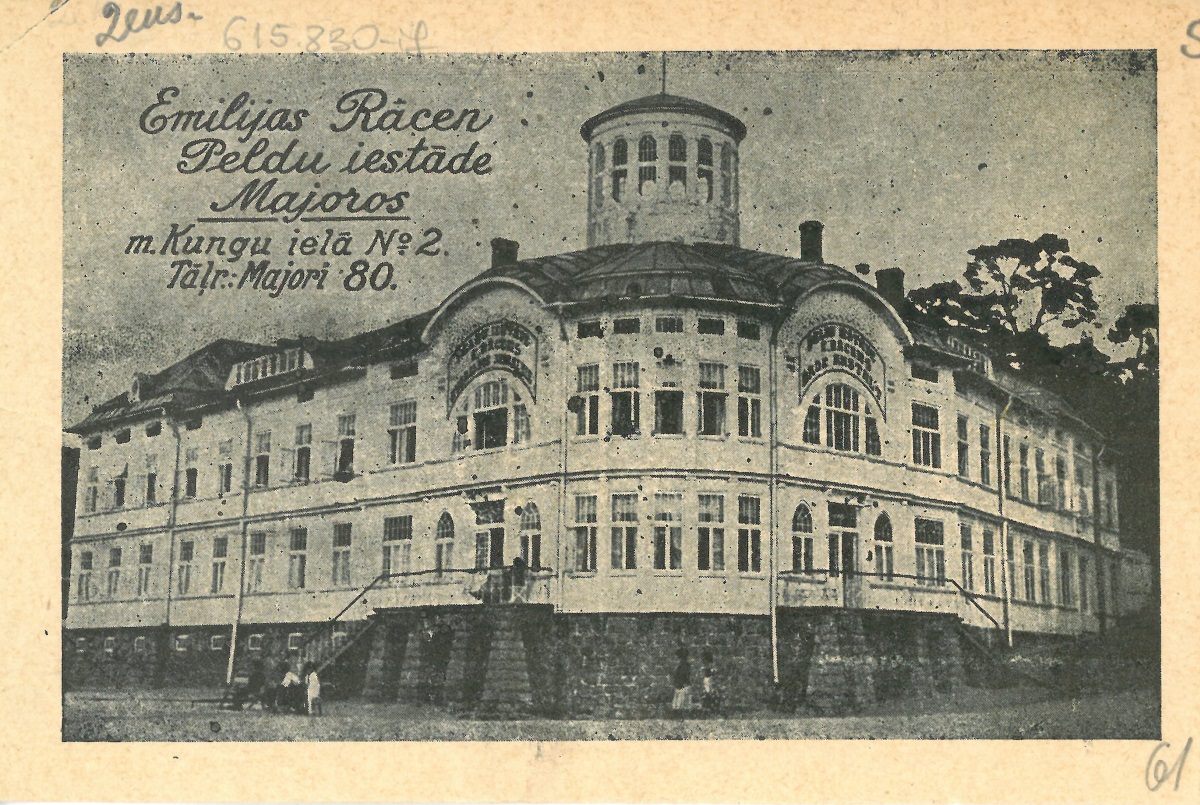

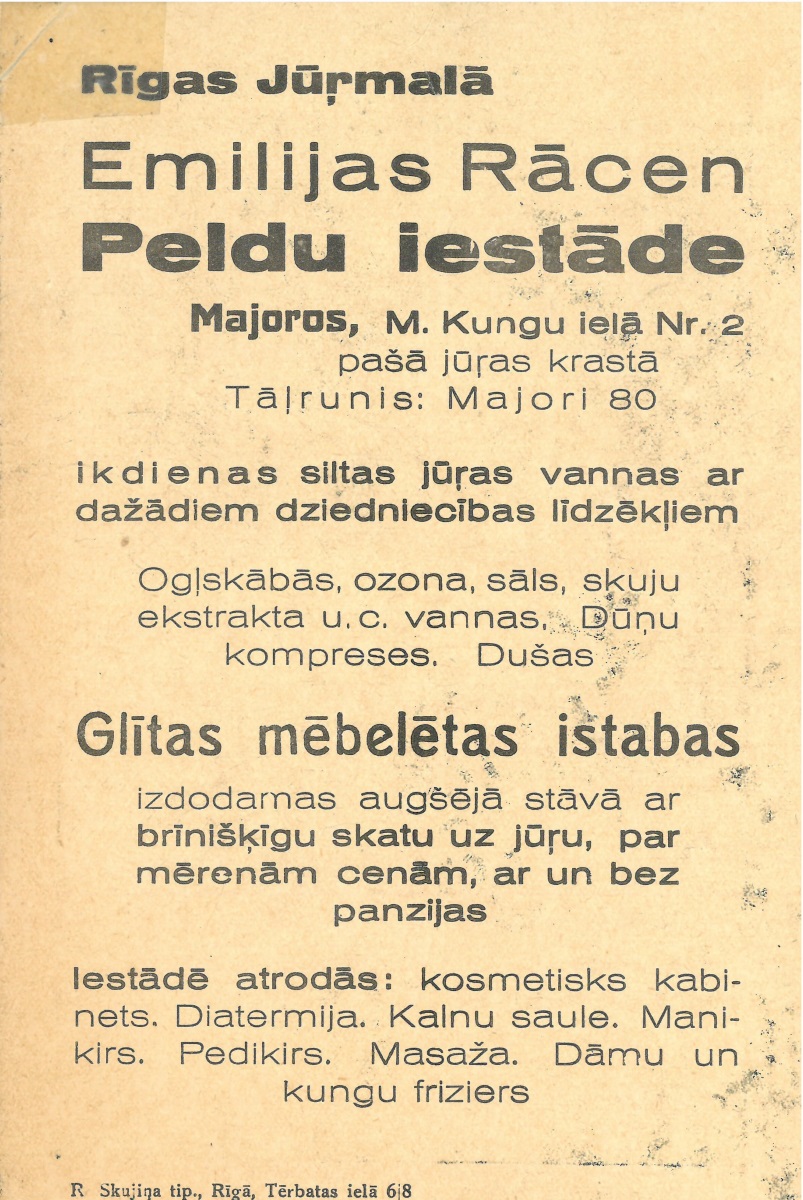

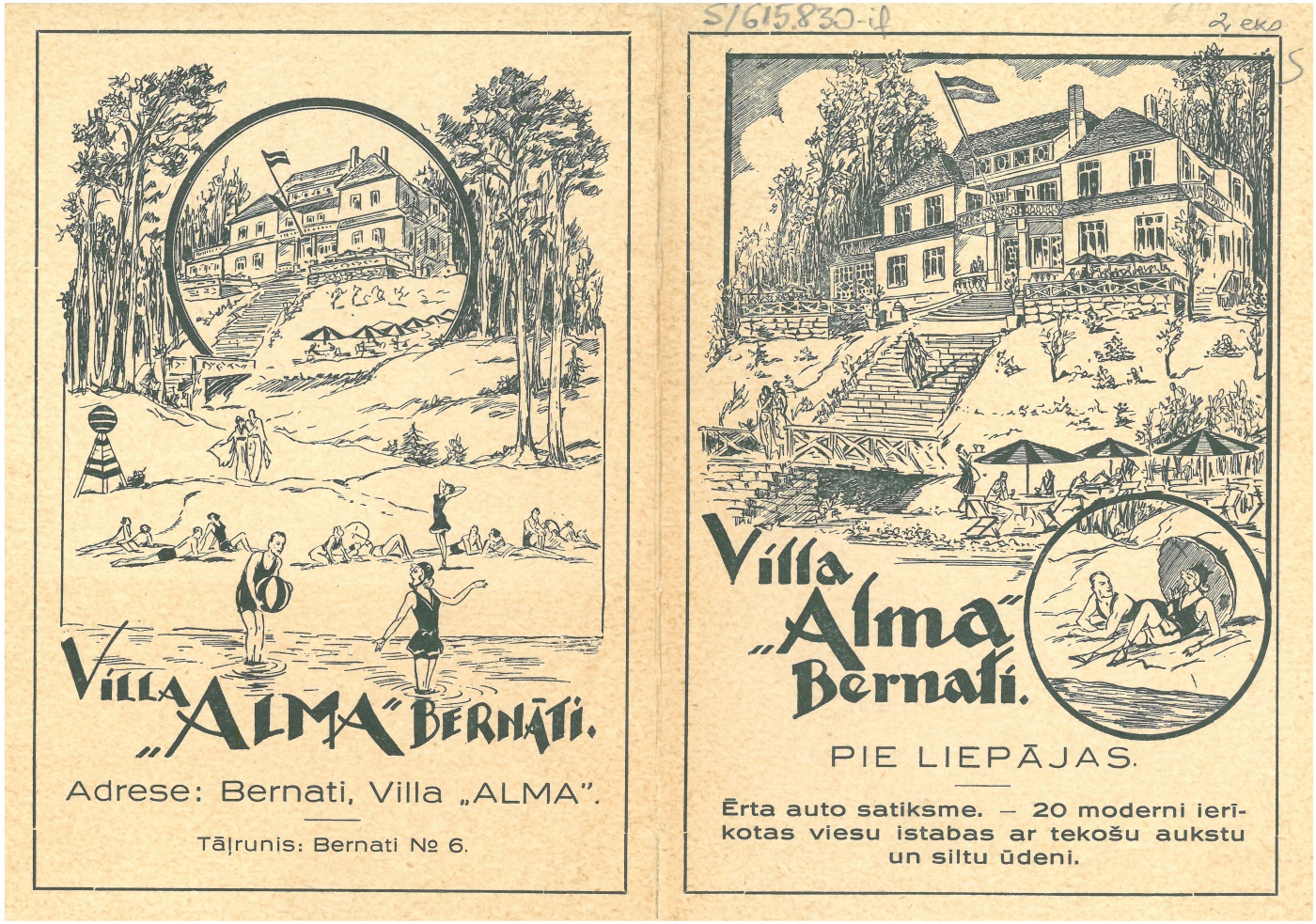

The cultural landscape of coastal area is rich and diverse as well. Disposition and the economy of the locals historically has been mainly connected with waters – the sea, lakes and the surrounding river mouths. Historically, these were fishing villages (zvejniekciemi) and ports, which are the basis of the today’s settlement structure of the coast. In the river-sea contact area many large port cities (Rīga, Liepāja, Ventspils) and port towns (Pāvilosta, Salacgrīva) have anchored and grown, as well as historical health resorts that have evolved into larger towns (Jūrmala, Saulkrasti). An important heritage of coastal lifestyle is the lighthouses, old fishing village buildings (for example, in Pape village), human-made tilths in-between dunes – “aizjomi” (in the Jūrmalciems surroundings), sea-side resort and seasonal villages (Ķemeri, Vecāķi, Plieņciems, Carnikava etc.), afforested dunes. From Ovīši to Ģipka spans the Liv Coast – the space of rich material and non-material cultural heritage of Liv culture.

“Just as in the olden days with the smile of victory the sea foams or crashes her waves against the coast, telling their stories about the Baltic amber, which was the jewellery of gods and roman women,” M. Sams writes about this symbolically significant sea resource. The history of amber in the Kurzeme coastal area mainly is linked with the territory from Liepāja to Palanga, where there were larger deposits and amber processing enterprises. However, amber can be found all over Kurzeme coastal area – mainly in the former sea inlets (nowadays lagoon lakes). In the 1920’s amber gained a symbolic significance – the Amber Coast (Dzintarkrasts) and the Amber Sea (Dzintarjūra) were the pictorial names of the landscape of coast and sea. However, the most symbolic translation of amber is the addressing the whole of Latvia as the Amber Land (Dzintarzeme), therefore emphasizing the national importance of the territory – its strategic border with the sea.

The strategic importance of the Baltic sea’s Kurzeme coastal region embodied also another space – the Soviet western border during the Cold War, metaphorically called “the Iron Curtain” that, especially along the coast, was a highly controlled militarized area. This coastal space with its historical objects (coastal artillery, aerodromes, surface-to-air missile bases, radio telescope, military towns, etc.) and historical development pathways is also a valuable part of coastal landscape’s heritage.

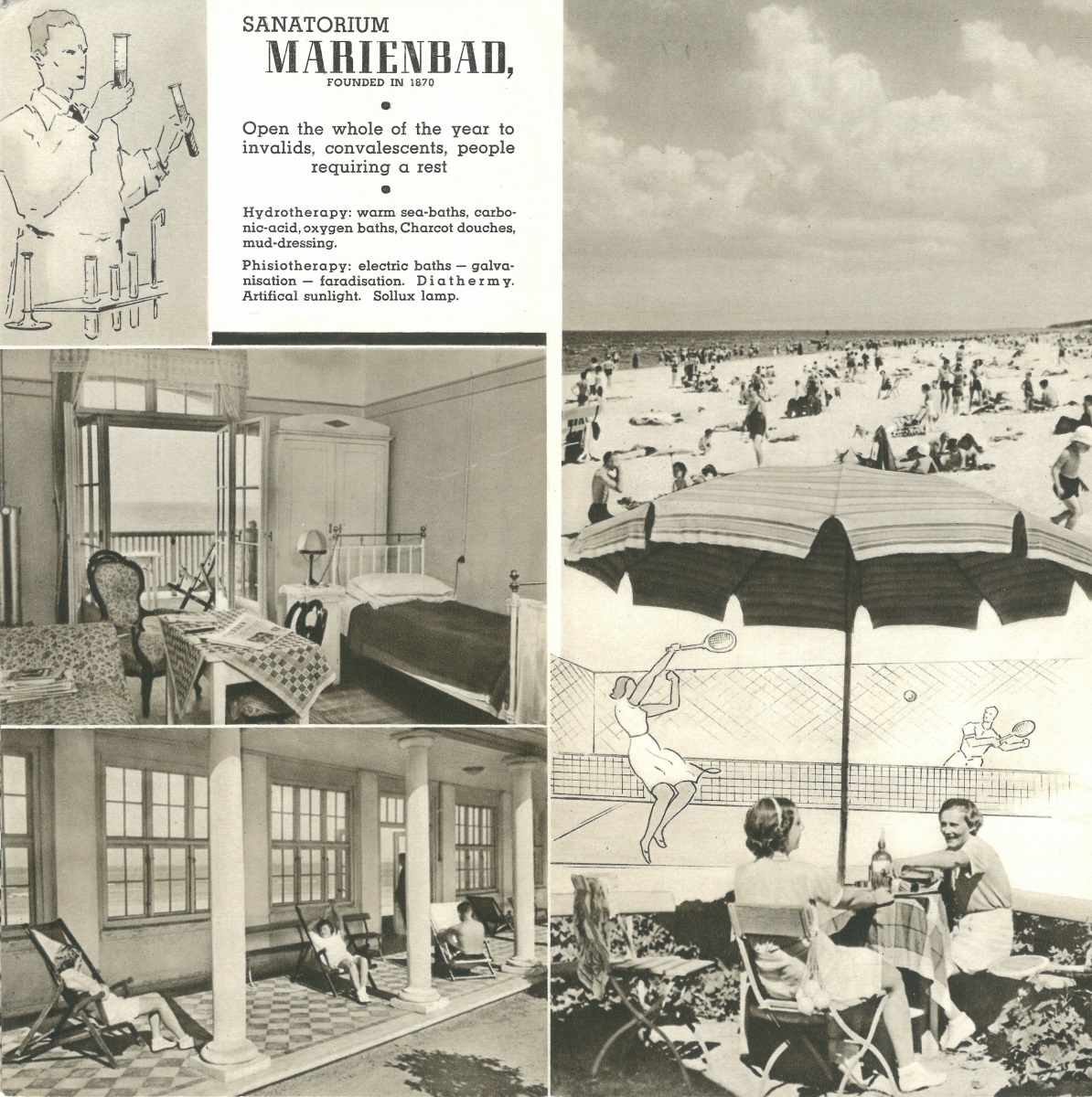

The coastal landscape during the 20th century has transformed into diverse recreational space, only in some places the everyday sea-dependent lifestyles have remained. The recreational value is an essential national capital, which is to be cared for and developed within the sustainable management framework, providing accessibility and preservation of natural, cultural and landscape values. Due to the climate change, a rising sea level and increased storm intensity is predicted, which can potentially damage the coastal landscape tremendously. Also, the creation of wind farms in the sea and on the land within the climate policy will change the coastal landscapes. However, this is the true nature of this dynamic landscape – strong and fragile at the same time, and which always will remain a space for sea and land interaction.

Anita Zariņa