The forest is an integral part of the Latvian landscape identity and cultural environment. Natural conditions and purposeful human interaction have determined that forests are the most important natural treasure of Latvia. They possess not only economical value, but they are home to many species of lichen, moss, plants, invertebrates, and birds and they serve a significant social function, providing people the possibilities of recreation and leisure activities.

As a result of human economical activities, the total forest area in Latvia has changed over time, but in landscape and culture they always have had a persistent value. For many years people have had an emotional connection with forest, created throughout centuries. The first written information about the territory of Latvia as, for instance, Livonian Chronicle of Henry (Heinrici Cronicon Lyvoniae), contains information of the significance of the Latvian landscapes and forests in the everyday life of the locals. For the tribes living in the territory of Latvia a tree was not only a raw material for tools and buildings; the wide and sometimes “dark” forests served as a hideout for locals in cases of attacks and a place of an ambush for troops, when waiting for the enemy. Forest and trees have been a “source of inspiration” for the people of Latvia, who created innumerable amounts of folk songs, legends, stories, fairy tales and riddles, that are an important part of the Latvian non-material heritage. Sacred forests and sacred trees, where “deities” live, served Latvians as cult objects.

Even nowadays many travellers have appreciated the huge significance of forests in the landscape of Latvia. French writer and publicist Jean-Paul Kauffmann, who travelled around Kurzeme, in his book “Courlande” (2011) points out: “the presence of forest, that is felt quite strongly”. In most of the cases it is hard to differ the Latvian landscape from the landscape of Latvian forests, because forests make up the Latvian landscape and cultural environment.

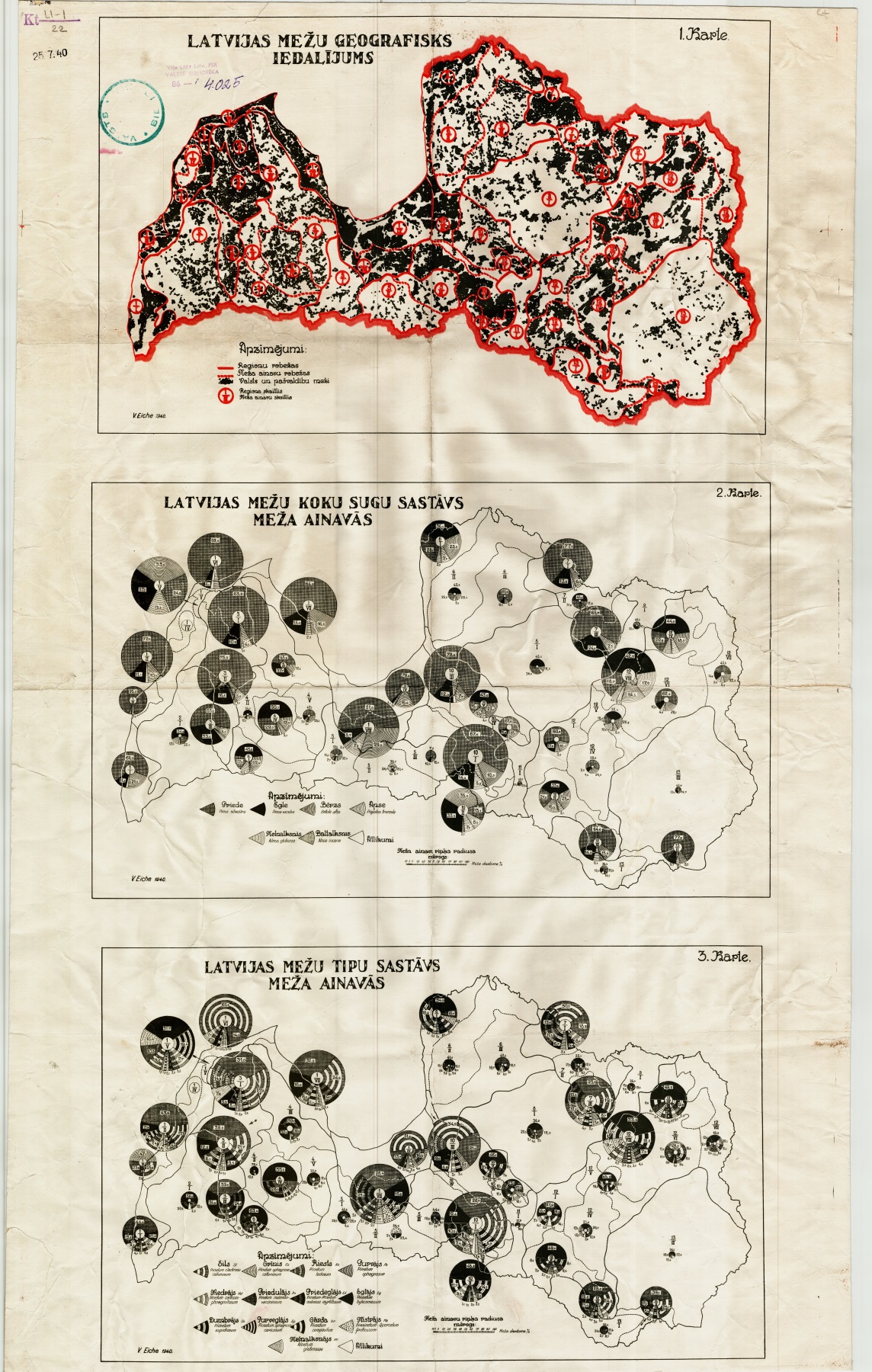

In the three-dimensional structure of Latvian landscape, we can differentiate the large tracts of forest, the small detached forests, clumps and individual trees. The large tracts of forest create the typical Latvian forest landscape, whereas the small detached forests, groups of trees and clusters – mosaic landscape. The forest landscape has huge diversity and variability in space and time. Its structure is determined by terrain and the rock it contains, the soil moisture content, forest crop content, as well as all natural and anthropogenic processes, that have made and continue making forest landscapes, that differ in content of forest crop species, economical value, importance in recreation and landscape design. In huge areas in the Latvian landscape the most common is the typical boreal coniferous forest, where pine trees and spruce trees are dominant. Pine tree forest landscapes are common in poor, sandy soils in coastal lowlands and in inland sandy soils as well. Inland dunes in the Strenči forest tract and other places have covered with lichen rich pine groves, where the dominant ground vegetation consists of white lichen – cladonia and cladina or reindeer lichen, which give the groves their white colour. Therefore, often these forest landscapes are called “the white grove”. In autumn, the blooming heathers catches the eye, and their creation historically has been largely affected by human interaction – forest fires and clearance crop-growing. The largest territory of heathers is in the military training facility in Ādaži, but heater fields are common in all coastal areas and other. Where soils get richer, in the forest crop next to pine trees spruce trees begin to appear. Relatively large areas in Latvia myrtillosa and vacciniosa forest type landscapes, where the growing stock is made up by pine trees, but in the understory or even in the canopy spruce trees are present. Myrtillosa and vacciniosa forest type landscapes are popular places to go berry-picking and mushrooming. Largest areas of this type of forests are common in the landscape regions of Piejūra, Ventaszeme, Gaujaszeme and Austrumzemgale. Very common in Latvia is a mixed type of pine tree and spruce tree forest (hylocomiosa) and they take up especially large areas in Ventaszeme, Rietumkursa, Austrumkursa, and Gaujaszeme landscape regions. The moist spruce type landscapes, which look the most beautiful in snowy winters, but attracts less people in summer, are the most common in Vidzeme highland and Austrumkursa landscape areas. Latvian forest landscape is also rich with hardwood trees, which give the landscape colourfulness and a variety of nuances. In Latgale highland and Austrumlatgale landscape areas and in the rest of the territory of Latvia the characteristics and design are influenced by birch groves, which in many places are formed on the lands of former agricultural lands. Whereas in Zemgale and Kurzeme both in pure stands and mixed forests very common are oak or aegopodiosa type forest landscapes.

The overview of Latvia’s forest landscapes is inconceivable without wetland forest types, which takes up 47,6% of all forests, from which almost half are drained. Wetland forest landscapes are less suitable for recreation, but they have a huge part in providing the biological diversity. However, walks through the marsh and forest trails (for, instance Black Alder Swamp Boardwalk in Ķemeri, Cena Moorland Footpath, marsh trails of Dunika and Planči, and other trails managed by The Nature Conservation Agency or Joint Stock Company “Latvia’s State Forests”) in the landscape of wetland forests, especially in spring or autumn, gives aesthetic pleasure.

Forest landscapes are in a continuous movement and they change throughout years and seasons. As a result of forest exploitation, the landscape is introduced with felled areas, then they are replaced by young growths, then seasoning stands and then by fully grown stands. Depending on the tree species, this cycle can take between 40 to 100 years, in many cases surpassing the human lifetime. In Latvian landscape the dominant age for forests is up to 100 years, but the specific weight of forests that are older than 100 years takes up only 11% of the total forest area. These forests are important in preserving the biological diversity and, thanks to their naturality, they have high diversity level of natural form and colour harmony and scientific value.

People feel the changes in the forest landscapes with all senses throughout the year. When seasons change, their colours and shades, sounds and smells changes along with them. These changes have inspired many artists, poets, writers and composers. Latvian State Forest Research Institute “Silava” research shows that forest landscapes or the element of forest landscapes can be seen in 19% of 20th and 21st century painted artworks by Latvian artists. Latvian landscapes of Vilhelms Purvītis (1972–1945) are inconceivable without the white birch trunks and the russet birch treetops in early spring; in the works of Rūdolfs Pinnis (1902–1992) forest landscapes are often seen portrayed in sunny days with a large spectrum of colours and use of light and shadows; in many paintings of Edgars Vinters (1919–2014) winter scenes are seen in a forest full of snow.

Part of Latvian forest landscapes are included in the specially protected natural areas, where they make up the largest part of protected areas. The huge significance of the preservation of biological diversity, influence of climate changeability, and providing human recreation is not achievable with only specially protected natural areas. The providing of different functions should be considered in forest landscape management and maintenance. Smart forest management is achieved by the ability of analysing the forest landscape.

Although no forest landscape has been included in the Latvian landscape treasures, their presence is felt in many selected landscapes by many Latvian residents and experts, such as Gauja River mouth with coastal dune forests, Veclaicene, Vecpiebalga hillocks, Mākoņkalns area and others.

The future of Latvian forest landscape depends on balancing various interests, because often different opinions meet on forest maintenance, nature protection, the need of human recreation and leisure time and the aesthetic principles. Only by listening and trying to understand opposite opinions it is possible to provide long-term forest landscape management and use for the needs of community.

Oļgerts Nikodemus