It is partially thanks to the density and quality of wooden buildings in Rīga that UNESCO has included the city’s historical centre in its World Heritage list. Still today, Rīga is estimated to be home to around 4000 wooden buildings. Some of the best known examples are at Kalnciems Quarter, a spot that residents and visitors have learned to love for its weekly farmers’ and crafts market, and summer street food festivals.

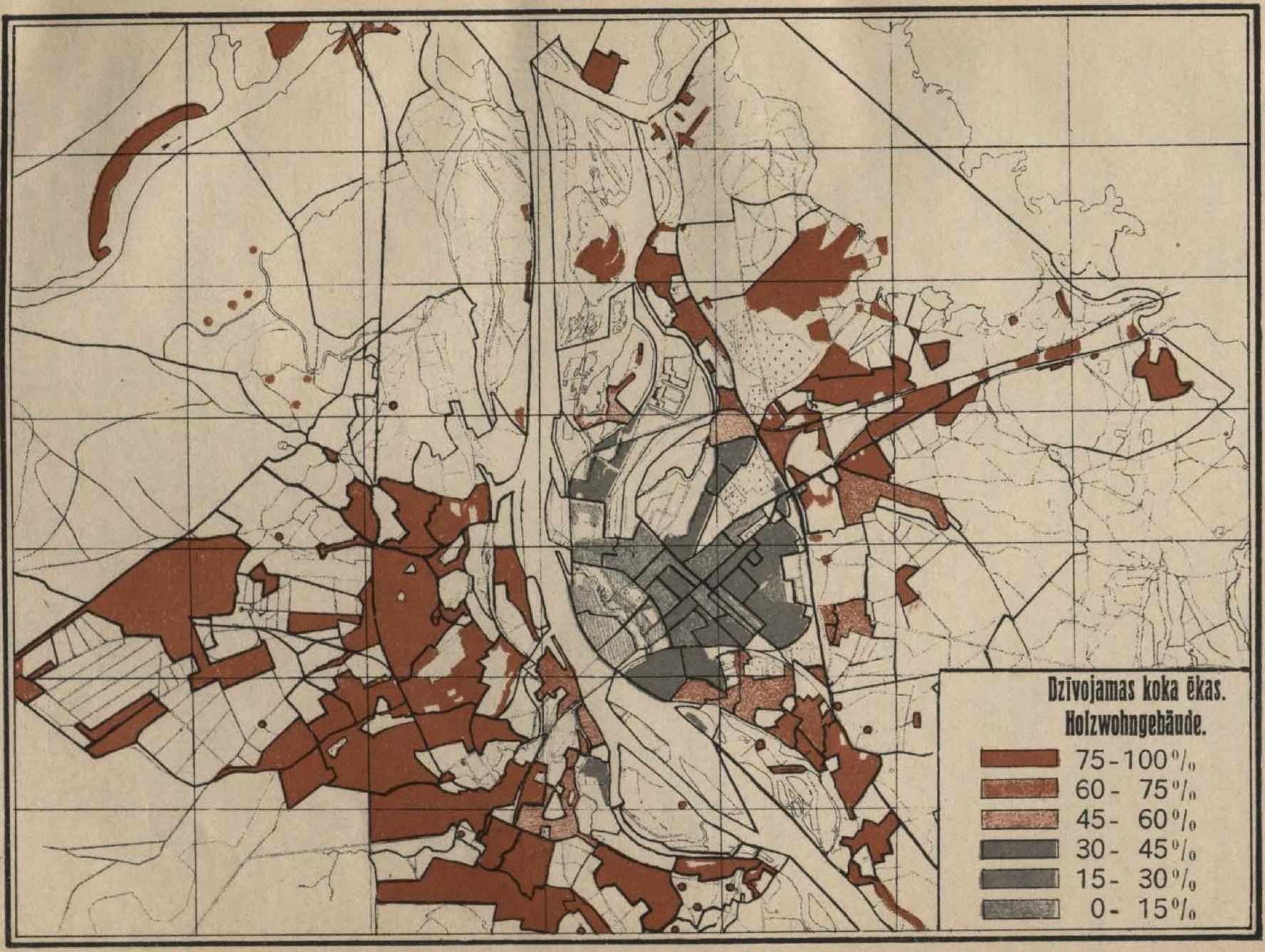

Wood has always been a common building material in Rīga. Until the late 17th century, even some of the buildings in the old town were constructed from wood or fachwerk. However, traditionally, when we speak about wooden buildings in Rīga, we speak more about residential areas, such as Ķīpsala, Āgenskalns, Grīziņkalns and Maskavas Forštate.

Rīga’s suburbs really began to flourish in the 1760s−90s when manor houses also appeared, and were mostly built of wood. Architect and historian Pēteris Blūms (1949) went as far as to deem 19th century Rīga a wooden metropolis with a stone heart (the old town).

In Rīga, wood remained a building material of choice for longer than other European cities. It was still used in the late 19th and early 20th century after the old town’s walls had been knocked down.

Between 1857 and 1863 the city got its famed boulevards, lined with five to six story stone buildings. Still today, some much lower wooden buildings stand proud among them and create an interesting contrast.

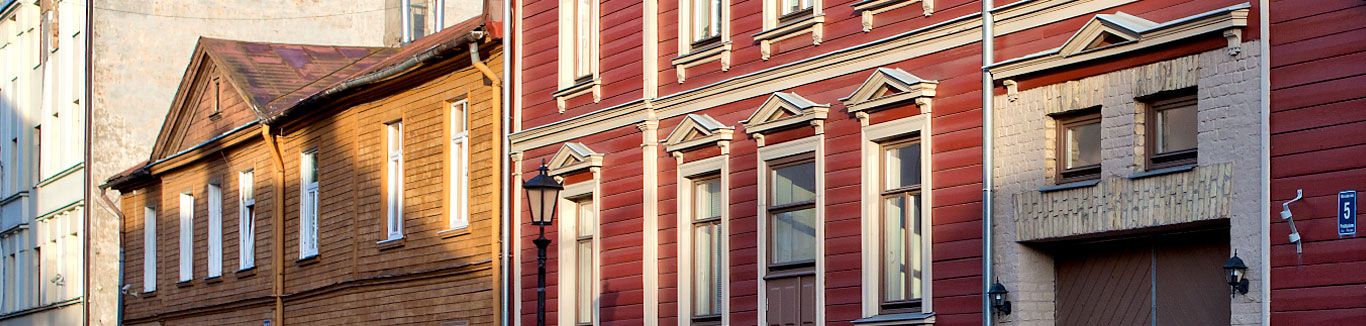

Many years of history and many different styles, such as baroque, classicism, historicism and art nouveau, are visible in the facades of Rīga’s wooden buildings. But their charm is particularly visible in the details, such as the window frames, doorways, pilasters, columns, shutters, cornices, attic windows.

Compared to other European cities, Rīga’s wooden buildings have suffered less from peace time fire damage but more from the war and intentional burning. The fire in 1812 is thought to have caused the worst damage.

With Napoleon’s army approaching, it was decided that some of the city’s suburbs should be burnt down. The fire caused unprecedented consequences as the flames spread to other parts of the city, burning down much more than planned.

Thankfully, a handful of 18th century wooden buildings still remain but the largest number date back to the 19th century when, after the great fire of 1812, most of Rīga’s suburban buildings were designed in keeping with the Russian Empire’s standards.

Nonetheless, though better known for their stone constructions in the city centre, even some of Latvia’s prime architects forayed into designing wooden buildings in the 19th and 20th centuries. Among them were Eižens Laube (1880−1967), Jānis Alksnis (1869−1939) and Aleksandrs Vanags (1873−1919).

It took a long time for Rīga’s wooden architecture to get the respect it deserves from both authorities and city residents. The 2001 Europa Nostra international organisation for the protection of cultural heritage conference on wooden architecture proved to be an important turning point. Thanks to the widespread publicity, presence of international experts in Rīga and discussions with local authorities, there was a noticeable shift in attitudes. It was also at this time that the “Koka Rīga” (Wooden Rīga) book came out.

The first to receive attention was the wooden architecture along Kalnciema Street, which is the most common route taken to get from the airport to the city. Here, the buildings were mostly built in the 18th and 19th centuries to house Rīga’s middle classes, and a lot of them are located between the bridge over the Rīga–Jūrmala railway line, and Slokas Street. Many of the buildings’ original features remain largely unchanged.

In 2006, the Rīga City Council, Ministry of Culture, Ministry of Defence, State Inspection for Heritage Protection and Latvia Nostra association created a public private partnership model for the preservation and maintenance of the historical wooden buildings. Latvia Nostra put together guidelines on painting facades, restoring and renovating both the outer shell and insides of the wooden buildings. Renovations are carried out with a lot of care and precision, and making sure that the building fits into its surrounding context.

Ķīpsala is a former fishing village and most of its original wooden buildings date back to the 19th century. In the late 1990s, the area was given a new lease of life by architect Zaiga Gaile (1951) and her partner, the businessman Māris Gailis (1951) who saw huge potential in Ķīpsala to become a desirable place to live.

In 1997, they built a new home for themselves here, which was followed by restoring a number of wooden buildings nearby. Eventually, some buildings were transported here from other parts of the city but their common characteristic is the quality of the restoration work and the way in which the historical outer shell is combined with contemporary living solutions and interior design.

Mūrnieku iela is in the formerly working class neighbourhood of Grīziņkalns. It is known for its predominantly two-story buildings built to house workers. What makes it unique in today’s context is the minor effects that the 20th century has left on the buildings. They remain largely true to their original form.

2003 was a good year for Mūrnieku Street as Rīga’s Latgale District Directorate launched its Mūrnieku Street regeneration project.

Ten years later, 2013 saw the founding of the council’s “Koka Rīga” (Wooden Rīga) centre for the renovation of wooden buildings. Here, city residents can receive advice on renovating, restoring and preserving wooden buildings and their original features.

Fortunately, more and more wooden buildings are being given the loving care and attention they need and deserve. After all, they are one of Rīga’s business cards.

Lelde Beņķe