Many people who come to Latvia comment on the beautiful, carefully tended graveyards dotting the country. Not just in the larger towns but also smaller villages, Latvian cemeteries are like sanctuaries or parks with well-manicured hedges surrounding family plots, shady trees, and benches for the elderly to sit, and pray, remembering their loved ones. Emphasis in graveyards is on making them feel homely, a place to want to go and visit, not avoid. A place to remember, maybe even share life’s joys and worries with one’s loved ones, a place to recharge, to also commune with nature. Failing to visit the cemetery and allowing the graves of one’s relatives to overgrow is frowned upon.

There is a whole seasonal cycle of Latvian traditions associated with cemeteries and remembrance of loved ones and one’s ancestors and they are not merely seen by locals as tradition more as “the natural order of things” that need to be adhered to so that the living and their ancestors co-exist in harmony. Some of the traditions predate Christianity yet are incorporated into the Christian rituals. For ancient Latvians, death was not considered a separator – rather a natural progression, aizsaulē or “behind the sun”. Foggy autumns were called the “time of deceased souls” (veļu laiks) – the time when, according to pagan beliefs, the departed come to visit the living and commune with them. This is also the time that Night of Candles (Svecīšu vakars) – or All Souls’ Day (Mirušo piemiņas diena) – when candles are lit all over Latvia in cemeteries by the graves of the departed, creating a mystical, yet comforting atmosphere. Remembering ancestors and the deceased in general, especially at this time is of utmost importance; there are pagan origins to this belief. After that – in winter through to spring, it is customary not to go into cemeteries and disturb the dead.

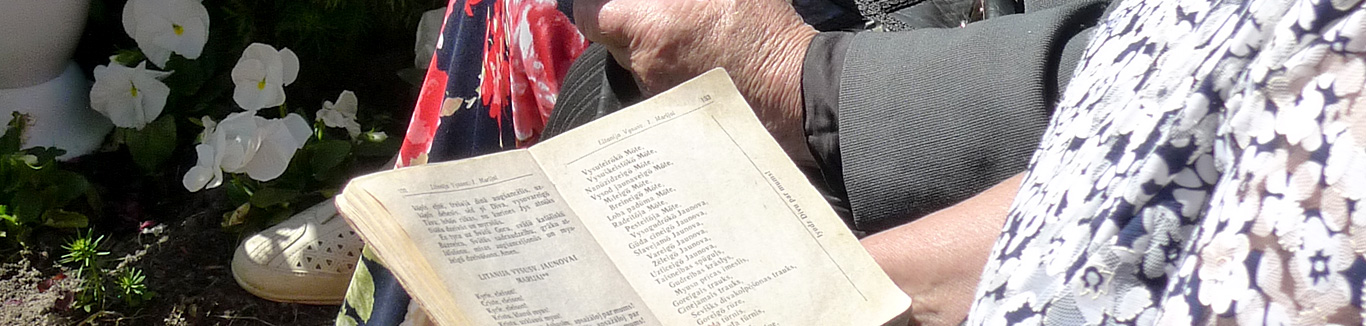

The main tradition that Latvians throughout all of Latvia follow still today is the traditional Cemetery Festival (Kapu svētki). Although it may sound morbid, they are not overly sombre occasions with the purpose to bring together not just members from the family, but whole clans (dzimtas) from one locality. Locals and ex-locals gather in the summer months from far and wide to attend the festival for one particular region. Here you don’t only come to remember and honour your deceased relatives but you get to meet other relatives and members of the local area who you may not have met for many years, catch up and reconnect. These are separate gatherings of Lutheran and Catholic congregations, often scheduled on the same day. The festivals feature a service which may be held in the cemetery and may be included as part of a town or regional festival. On the same evening it is common for locals to meet and enjoy themselves at the town’s open-air dance (zaļumballe).

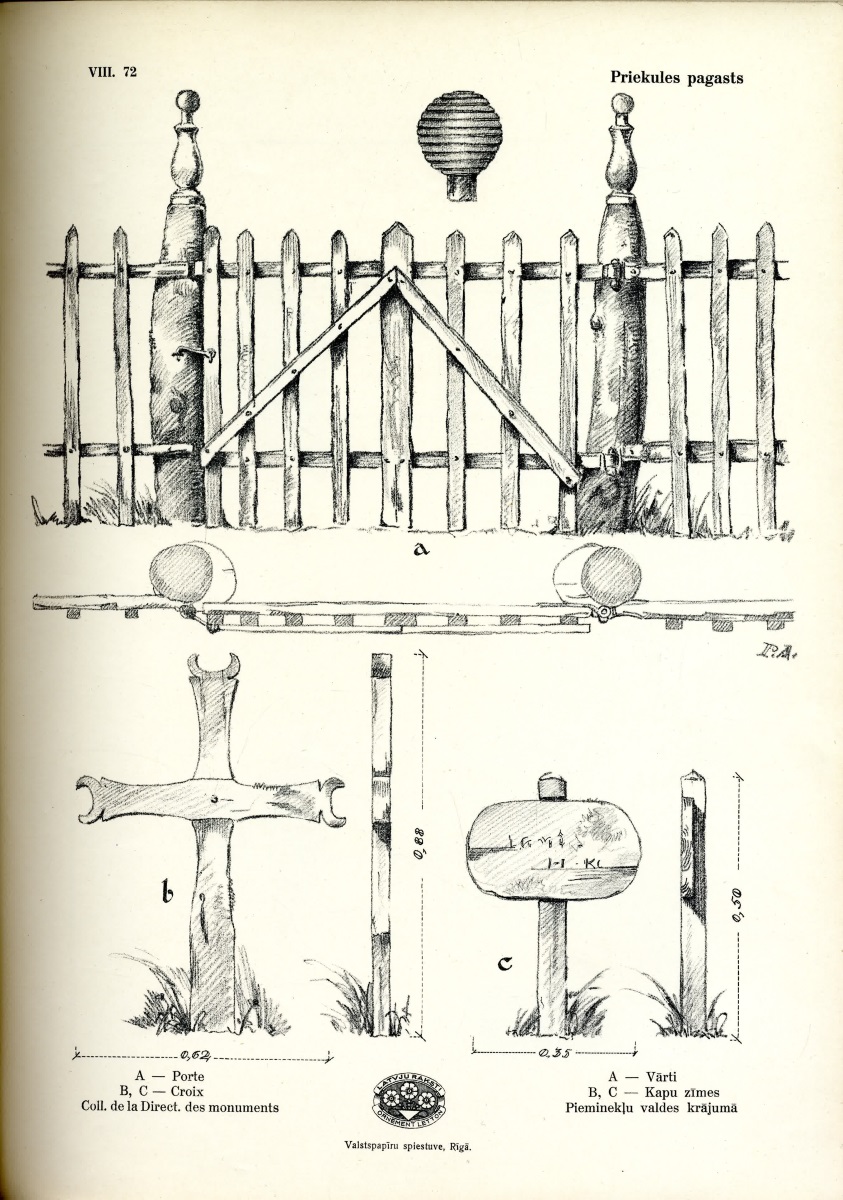

Latvian graveyard traditions are a mix of pre-Christian, Christian and secular traditions. Traditions are associated with regular visits to prune shrubbery and tend to and plant new flowers by the gravestones, raking of leaves. In autumn there is a different list of jobs; the clearing of graves of fallen leaves, placing of candles, wreaths and pine branches on the graves instead of cut flowers, raking of the grave site. Raking is a very big part of tending to a grave – according to tradition, no footsteps must be visible on the ground after leaving the grave site. Another tradition – not to bring flowers (or anything else) home from the cemetery is a remnant from the pagan belief that the two worlds – that of the living and that of the dead should not be mixed – and this order must be maintained so as not to cause bad luck.

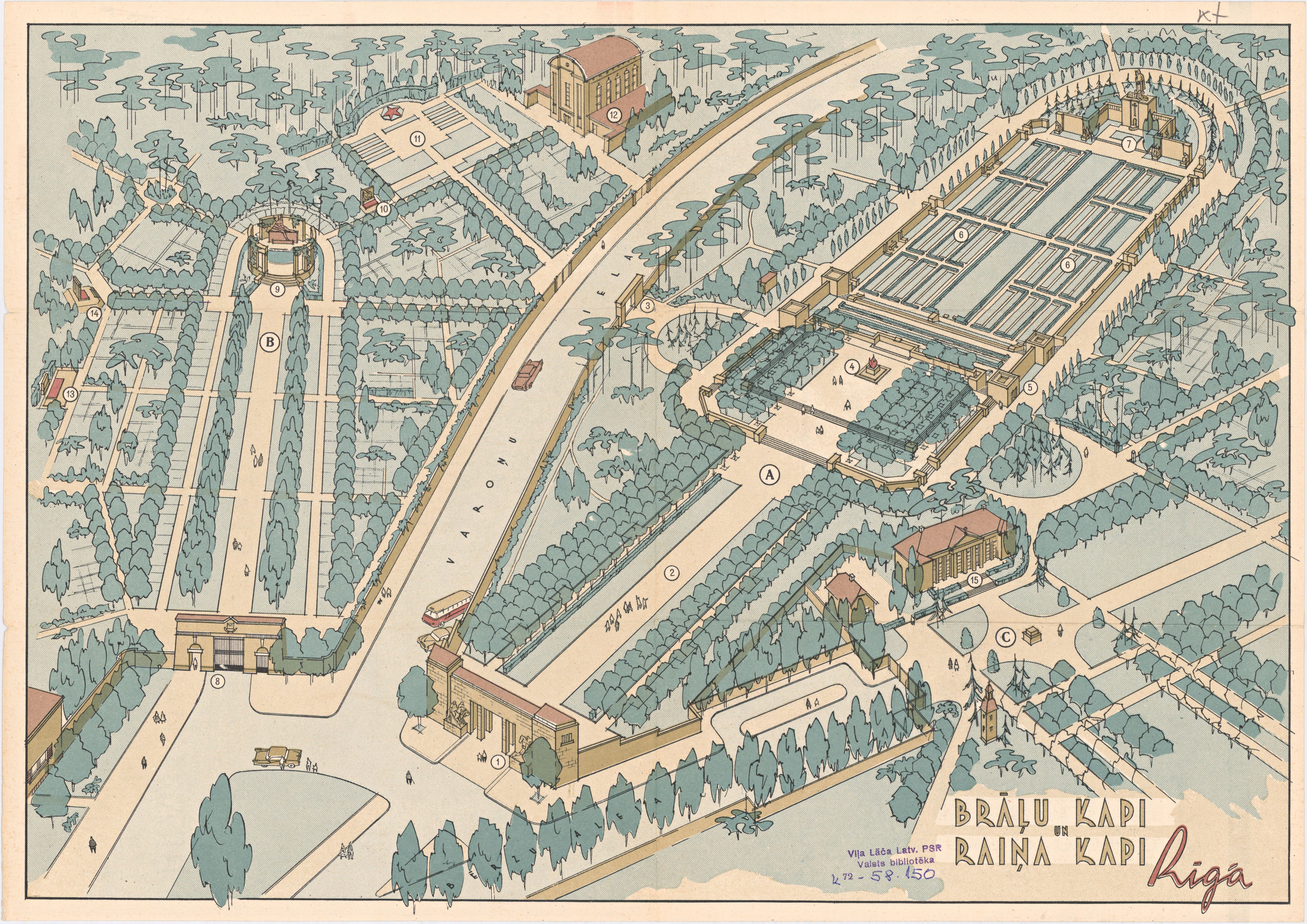

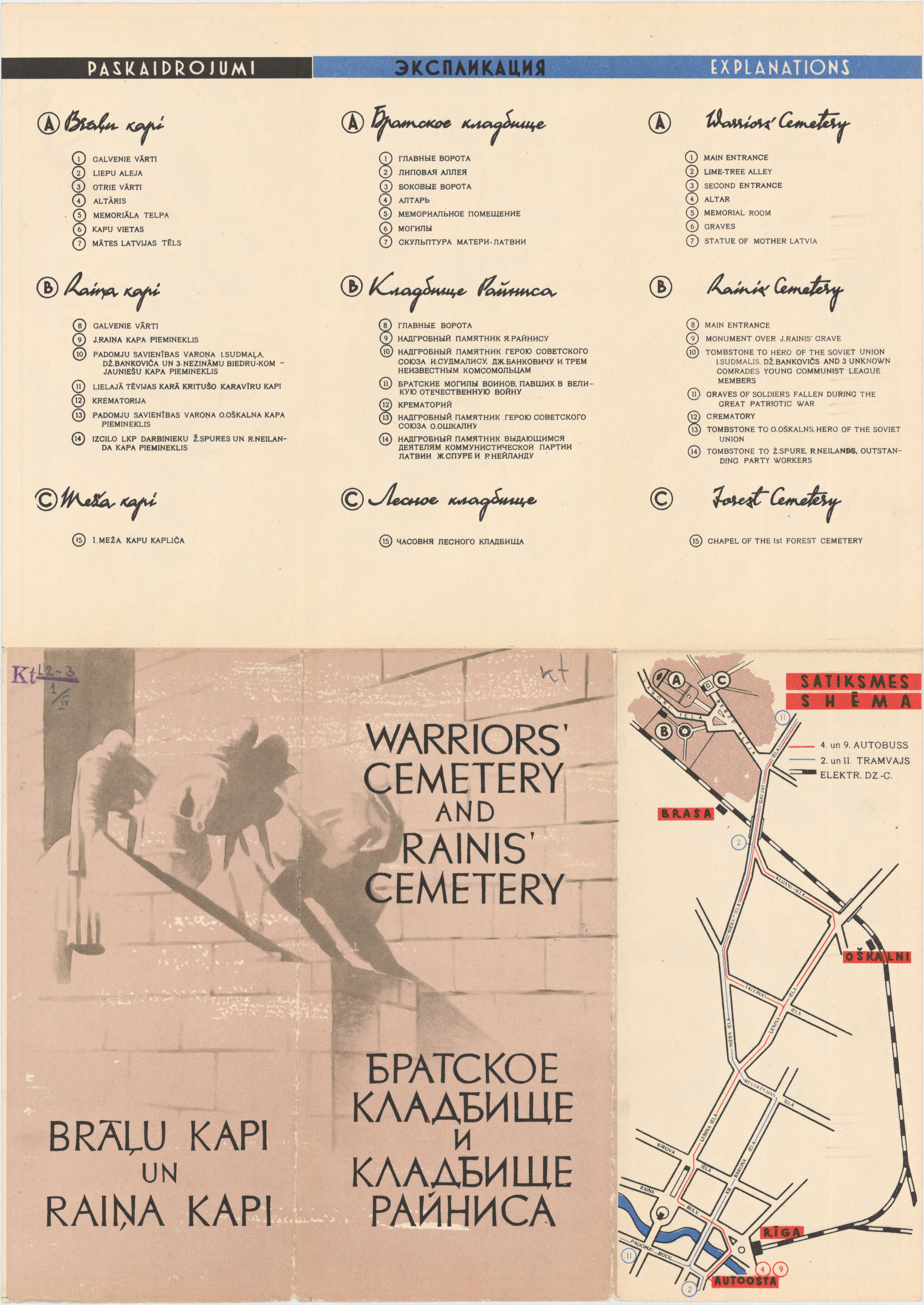

The larger cemeteries in Rīga, such as the Brothers Cemetery (Brāļu kapi), the Forest Cemetery (Meža kapi) or the Rainis Cemetery (Raiņa kapi) all have national significance as these are hallowed ground – the final resting place of famous statesmen, national poets and writers, artists and composers who are revered as well as soldiers who have lost their lives for their country. The Brothers Cemetery and other cemeteries with memorials for soldiers who died in both World Wars are places where annual national commemoration events take place, on Lāčplēsis Day (Lāčplēša diena) in particular, the memorial day for soldiers who fought for the independence of Latvia at the end of World War I.

Daina Gross