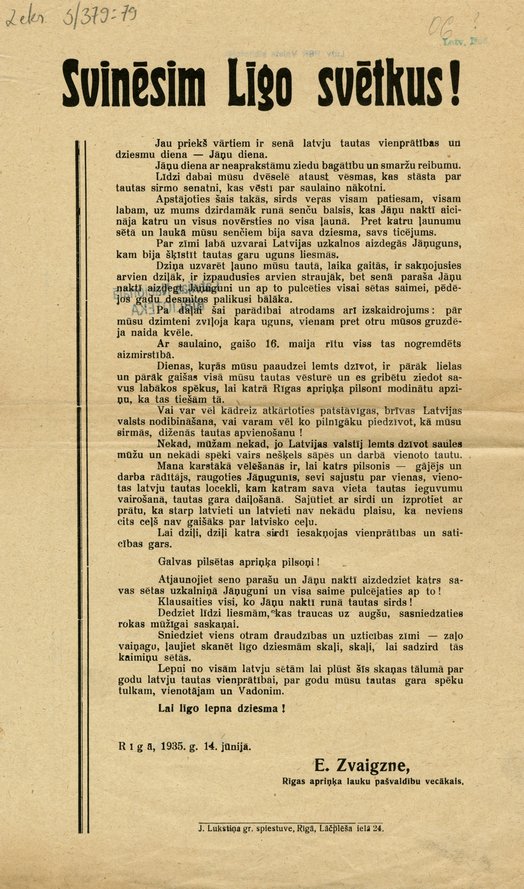

Dating back many centuries, Jāņi traditions can be gleaned from numerous Latvian folksongs, passed down by word-of-mouth. Modern-day festivities are the reconstruction of ancient tribal rituals performed on the territory that is now Latvia during the summer solstice; a fertility ritual for ancient Latvian farmers and a part of the sun cult. Pagan tribes all over Europe celebrated the height of summer before Christian traditions took their place. While Latvia is now a Christian nation, there is an interest in renewing some aspects of the pagan traditions as a form of national pride, and since the restoration of independence of Latvia in 1990 many Latvians have embraced celebrating Jāņi with a spirit of reverence for ancient traditions.

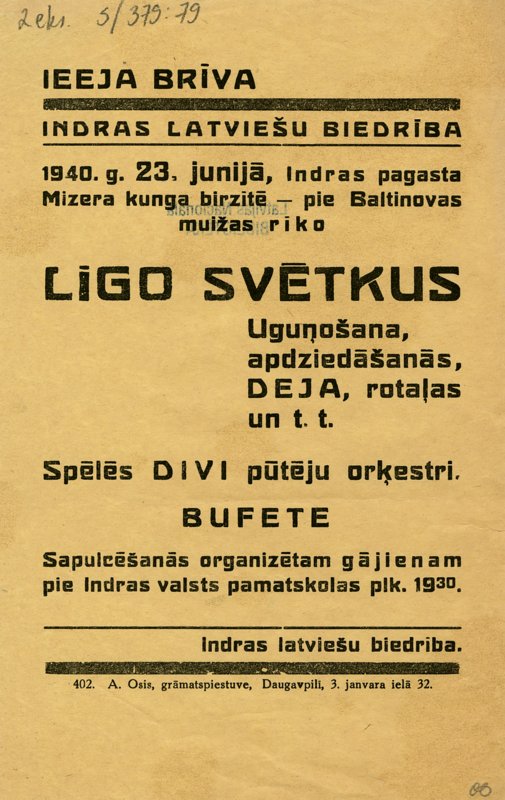

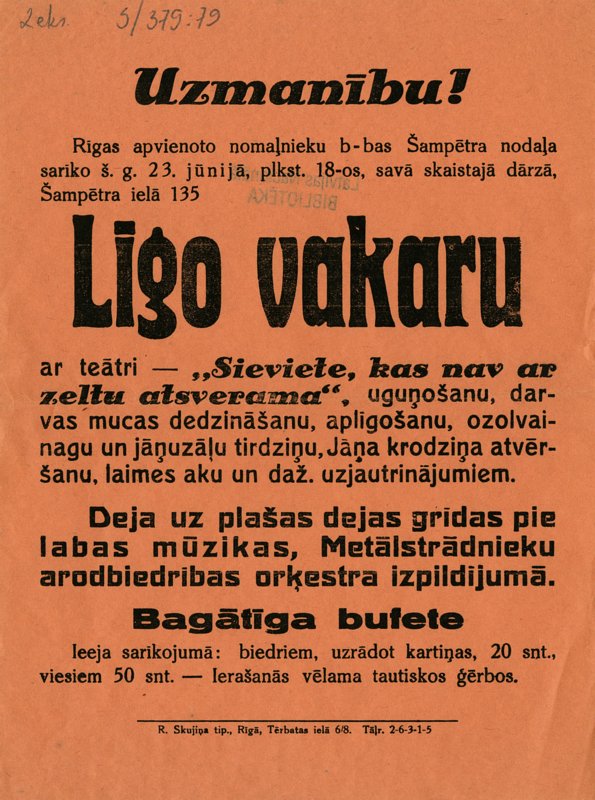

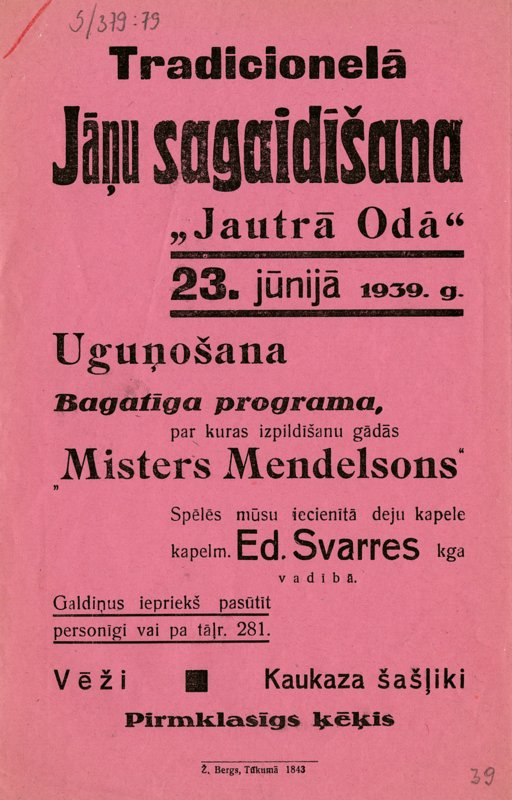

During the Soviet era, there was a rather inconsistent and negative attitude from the Soviet ruling class towards the celebration of Jāņi – at first it was forbidden, then celebrations were allowed but with a Soviet touch. The celebrations increasingly became a reason to get together for a country dance (zaļumballe), or an excuse to drink to excess and eat skewered meat (šašliki), and to jump over the Jāņi bonfire. The aim was for the original meaning to be forgotten and extinguished over time.

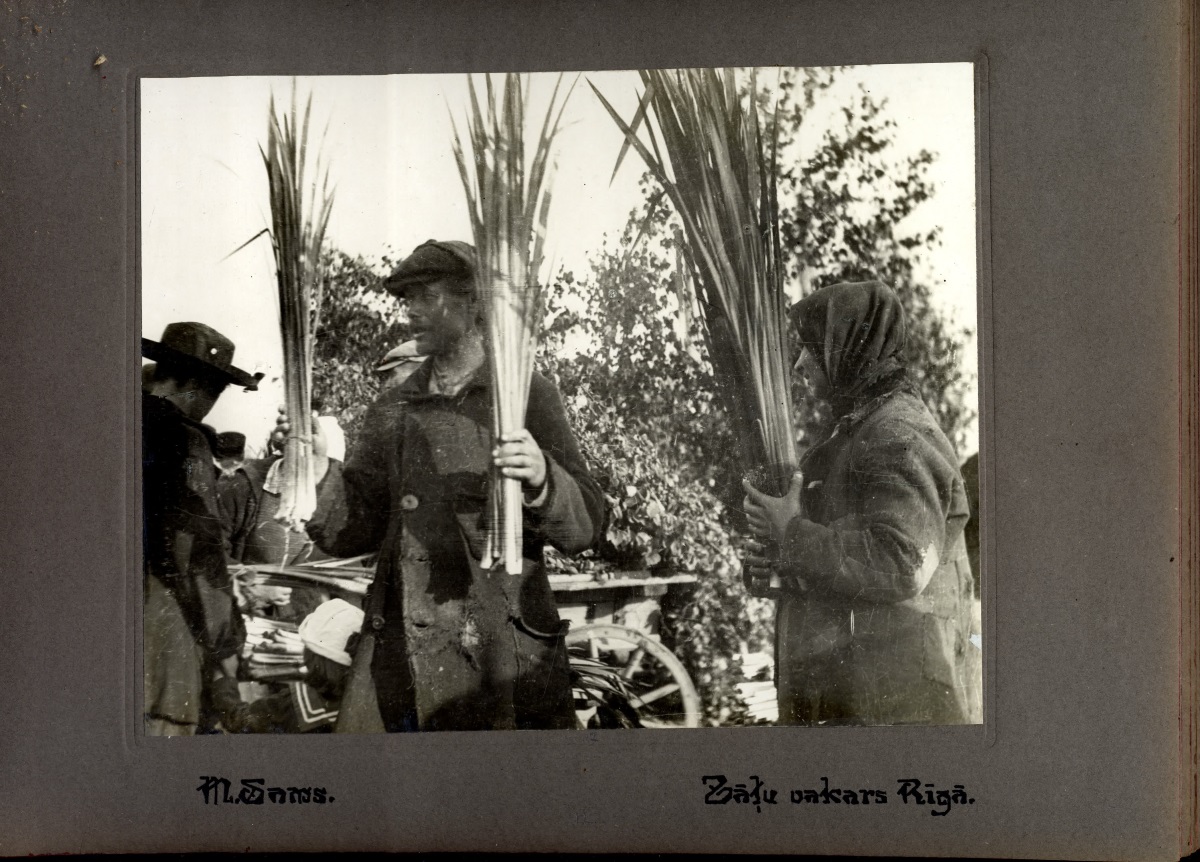

Nowadays, although many still do celebrate this holiday in mass concerts and dances, there is a trend for people to treat this celebration with seriousness and preparations are made weeks ahead. Most people celebrate in the countryside – on country properties, where it is more conducive to performing rituals that the celebrations were originally intended for. Properties are tidied and swept, yards and fields cleared, houses and auxiliary buildings (even livestock) are decorated with birch branches, oak and floral wreaths so that the Jāņa bērni (Jānis’ children – in other words – guests) feel welcome and the property is blessed by their presence. Special round-shaped cheese with carraway seeds (Jāņu siers) is prepared, bacon buns (pīrāgi) and other pastries baked by the hostess – or Jāņa māte – and beer (alus) brewed by the host – or Jāņa tēvs.

These days guests also bring along their own food to share, and tents to sleep in. In many households, everyone – hosts and guests – wears their national costume, if they own one, or a modified version of one. The unique Latvian way of celebrating is singing folksongs for hours with the refrain “līgo” or “rotā”, with each folksong sung for a different and significant reason. In some households the elderly know the songs off by heart, in most cases, though print outs of songs, songbooks – or even apps – on a mobile phone serve as the basis of the night’s singing.

Women wear flower garlands on their heads, handwoven with flowers and grasses found in the surrounding fields. All women – married or unmarried – are permitted to wear a garland (and not the traditional caps or scarves that married women usually wear), and men – wreaths made of oak leaves. Many ancient rituals are now being rejuvenated, although they may have a modern interpretation, as the meaning of many rituals can often only be guessed by our 21st century mind. Some rituals are associated with predicting the future, others with keeping evil spirits at bay, others are fertility rites – for the harvest, livestock and youth in a household, still others – to bring blessings and good fortune into the household. Jāņi celebrations are about man and nature blending together as one – man by his ritual actions hoping to gain the benevolence of the gods of nature that have the power to influence people’s lives.

Daina Gross